I’m aware that I haven’t done a good job of describing Carroll’s AIT. Last week, I bought a Kindle version of Sharwood Smith and Truscott’s (2014) The Multilingual Mind (currently on offer for 19 euros – hurry, hurry) which presents their MOGUL (Modular On Line Growth and Use of Language) theory, and I’m very inpressed with its coherence, cohesion and readability. It relies partly on Jackendoff, and briefly describes Carroll’s AIT much more succinctly than I’ve managed. I highly recommend the book,

I’ll continue examing bits of AIT and its implications, before trying to make sense of the whole thing and reflect on some of the disagreements among those working in the field of SLA. In this post, I’ll look at Carroll’s AIT in order to question the use by many SLA theories of the constructs of input, intake, and noticing.

Recall that Jakendoff’s system comprises two types of processor:

- integrative processors, which build complex structures from the input they receive, and

- interface processors, which relate the workings of adjacent modules in a chain.

The chain consists of three main links: phonological, syntactic, and conceptual/semantic structure, each level having an integrative processor connected to the adjacent level by means of an interface processor.

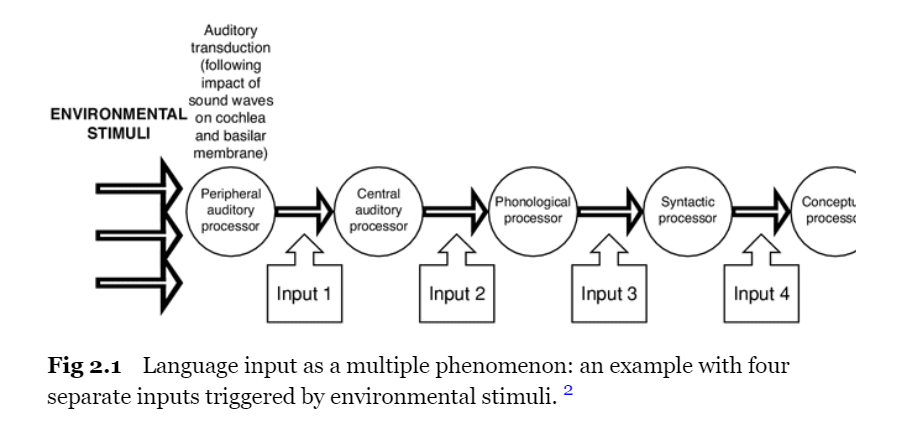

Carroll takes Jackendoff’s theory and argues that input must be seen in conjunction with a theory of language processing: input is the representation that is received by one processor in the chain.

Thus, Carroll argues, the view of ‘input from outside’ is mistaken: input is a multiple phenomenon where each processor has its own input, which is why Carroll refers to ‘environmental stimului’ to denote the standard way in which ‘input’ is seen. Stimuli only become input as the result of processing, and learning is a function not of the input itself, but rather of what the system does with the stimuli. In order to explain SLA, we must explain this system. Carroll’s criticism is that the construct ‘input’ is used in many theories of SLA as a cover term which hides an extremely complex process, beginning with the processing of acoustic (and visual) events as detected by the learner’s sensory processing mechanisms.

Carroll’s view is summarised by Sharwood Smith and Truscott, 2014, p. 212) as follows:

The learner initially parses an L2 using L1 parsing procedures and when this inevitably leads to failure, acquisition mechanisms are triggered and i-learning begins. New parsing procedures for L2 are created and compete with L1 procedures and only win out when their activation threshold has become sufficiently low. These new inferential procedures, adapted from proposals by Holland et al. (1986), are created within the constraints imposed by the particular level at which failure has taken place. This means that a failure to parse in PS [Phonological Stuctures], for example, will trigger i-learning that works with PS representations that are currently active in the parse and it does so entirely in terms of innately given PS representations and constraints, hence the ‘autonomous’ characterisation of AIT (Holland et al. 1986, Carroll 2001: 241–2).

Of course, the same process described for PS is applied to each level of processing.

Both parsing, which takes place in working memory, and i-learning, which draws on long-term memory, depend, to some extent on innate knowledge of the sort described by Jackendoff, where the lexicon plays a key role, incorporating the rules of grammar and encoding relationships among words and among grammatical patterns.

Jackendoff’s theory supposes that just about everything going on in the language faculty happens unconsciously – it’s all implicit learning – and Carroll’s use of Holland et al.’s theory of induction is similarly based on implicit learning.

So what does all this say about other processing theories of SLA?

Here’s Krashen’s model:

Any comprehensible input that passes through the affective filter, gets processed by UG and becomes acquired knowledge. Learnt knowledge acts as a monitor. Despite the fact that it has tremendous appeal, the model is unsatisfactory because none of these stages is described by clear constructs, and the theory is hopelessly circular. McLaughlin (1978) and Gregg (1984) provide the best critique of this model.

Then we have Schmidt’s Noticing Hypothesis

Here again, input is never carefully defined – it’s just the language that the learner hears or reads. What’s important, for Schmidt, is “noticing”. This is a gateway to “intake”, defined as that part of the input consciously registered and worked on by the learner in “short/medium-term memory (I take this to be working memory) and which then gets integrated into long-term memory, where it develops the interlanguage of the learner. So noticing is the necessary and sufficient condition for L2 learning.

I’ve done several posts on Schmidt’s Noticing Hypothesis (search for them in the Search bar on the right), so here let me just say that it’s now generally accepted that ‘noticing’, in the sense of conscious attention to form, is not a necessary condition for learning an L2: the hypothesis is false. The ammended, much weaker version, namely that “the more you notice the more you learn” is a way of rescuing the hypothesis, and has been, in my opinion, too quickly accepted by SLA scholars. I’m personally not convinced that even this weak version can be accepted; it needs careful refinement, surely. In any case, Schmidt’s model makes the same mistake as Krashen’s: in starting with an undefined construct of input, it puts the cart before the horse. (Note that this has nothing to do with Scott Thornbury’s judgement on UG, as discussed in an earlier post.) As Carroll says, we must start with stimuli, not input, and then explain how those stimuli are processed.

Finally, there’s Gass’s Model (1997), which offers a more complete picture of what happens to ‘input’.

Gass says that input goes through stages of apperceived input, comprehended input, intake, integration, and output, thus subdividing Krashen’s comprehensible input into three stages: apperceived input, comprehended input, and intake. Gass stresses the importance of negotiated interaction in facilating the progress from apperceived input to comprehended input, adopting Long’s construct of negotiation for meaning which refers to what learners do when there’s a failure in communicative interaction. As a result of this negotiation, learners get more “usable input”, they give “attention” (of some sort) to problematic features in the L2, and make mental comparisons between their IL and the L2 which leads to refinement of their current interlanguage.

But still, what is ‘apperceived input’? Gass says it’s the result of ‘attention’, akin to Tomlin and Villa’s (1994) construct of ‘orientation’; and Schmidt says it’s the same as his construct of ‘noticing’. So is it a concious process, then, taking place in working memory? Just to finish the story, Long, in Part 4 of this exploration of AIT says this:

Genuinely communicative L2 interaction provides opportunities for learners focused on meaning to pick up a new language incidentally, as an unintended by-product of doing something else — communicating through the new language — and often also implicitly, i.e., without awareness. Interacting in the L2 while focused on what is said, learners sometimes perceive new forms or form-meaning-function associations consciously — a process referred to as noticing (Schmidt, 1990, 2010). On other occasions, their focus on communication and attention to the task at hand is such that they will perceive new items in the input unconsciously — a process known as detection (Tomlin & Villa, 1994). Detection is especially important, for as Whong, Gil, & Marsden (2014) point out, implicit learning and (barring some sort of consciousness-raising event)the end-product, implicit knowledge, is what is required for real-time listening and speaking.

Long makes a distinction betwween ‘implicit’ and ‘incidental’ learning. ‘Implicit’ means unconscious, while ‘incidental’, I think, means conscious, and refers to Schmidt’s ‘noticing’. Long then says that ‘implicit’ learning, whereby “learners perceive new items in the input unconsciously” and is explained by “a process known as detection (Tomlin & Villa, 1994)”, is “especially important”, because “implicit knowledge is what is required for real-time listening and speaking”.

So here we have yet another construct: ‘detection’. ‘Detection’ is the final part of Tomlin and Villa’s (1994) three-part process of ‘attention’. Note first that they claim that ‘awareness’( defined as “the subjective experience of any cognitive or external stimulus,” (p. 194), and which is the crucial part of Schmidt’s ‘noticing’ construct) can be dissociated from attention, and that awareness is not required for attention. With regard to attention, three functions are involved: alertness, orientation, and detection.

Alertness = an overall, general readiness to deal with incoming stimuli or data.

Orientation = the attentional process responsible for directing attentional resources to some type or class of sensory information at the exclusion of others. When attention is directed to a particular piece of information, detection is facilitated.

Detection = “the cognitive registration of sensory stimuli” and is “the process that selects, or engages, a particular and specific bit of information” (Tomlin & Villa, 1994, p. 192). Detection is responsible for intake of L2 input: detected information gets further processing.

Gass claims that “apperceived input” is conscious, the same as Tomlin and Villa’s ‘orienation’, but is Gass’s third stage ‘comprehended input’ the same as ‘Tomlin and Villa’s ‘detection’? Well, perhaps. ‘Comprehended input’ is “potential intake” – it’s information which has the possibility of being matched against existing stored knowledge, ready for the next stage, ‘integration’ where the new information can be used for confirmation or reformulation of existing hypotheses. However, if detection is unconscious, then comprehended input is also unconscious, but Gass insists that comprehended input is partly the result of negotiation of meaning, which, Long insists involves not just detection but also noticing.

This breaking down of the construct of attention into more precise parts is supposed to refine Schmidt’s work. Schmidt starts with the problem of conscious versus uncoscious learning, and breaks ‘consciousness’ down into 3 parts: consciousness as awareness; consciousness as intention; and consciousness as knowledge. As to awareness, Schmidt distinguishes between three levels: Perception, Noticing and Understanding, and the second level, ‘noticing’, is the key to Schmidt’s eventual hypothesis. Noticing is focal awareness. Trying to solve the problem of how ‘input’ becomes ‘intake’, Schmidt’s answer is crystal clear, at least in its initial formulation: ‘intake’ is “that part of the input which the learner notices … whether the learner notices a form in linguistic input because he or she was deliberately attending to form, or purely inadvertently. If noticed, it becomes intake (Schmidt, 1990: 139)”. And the hypothesis that ‘noticing’ drives L2 learning is plain wrong.

Tomlin and Villa want to recast Schmidt’s construct of noticing as “detection within selective attention”.

Acquisition requires detection, but such detection does not require awareness. Awareness plays a potential support role for detection, helping to set up the circumstances for detection, but it does not directly lead to detection itself. In the same vein, the notion of attention to form articulated by VanPatten (1989, 1990, in press) seems very much akin to the notion of orientation in the attentional literature; that is, the learner may bias attentional resources to linguistic form, increasing the likelihood of detecting formal distinctions but perhaps at the cost of failing to detect other components of input utterances. Finally, input enhancement in instruction, the bringing to awareness of critical form distinctions, may represent one way of heightening the chances of detection. Meta- descriptions of linguistic form may help orient the learner to salient formal distinctions. Input flooding may increase the chances of detection by increasing the opportunities for it” (Tomlin and Villa, 1994, p. 199).

Well, as far as as forming part of a coherent part of a theory of SLA is concerned, I don’t think Tomlin and Villa’s treatment of attention stands up to scrutiny, for all sorts of reasons, many of them teased out by Carroll. Nevertheless, the motivation for this detailed attempt to understand attention, apart from carrying on the work of refining processing theory, is clearly revealed in the above quote: what’s being proposed is that L2 learning is mostly implicit, but that this implicit learning needs to be supplemented by occasional, crucial, conscious attention to form, which triggers ‘orienation’ and enables ‘detection’. An obvious pay off is the improved efficaciousness of teaching! And that, I think, is at the heart of Mike Long’s view – and of Nick Ellis’ , too.

But it doesn’t do what Carroll (2001, p. 39) insists a theory of SLA should do, namely give

- a theory of linguistic knowledge;

- a theory of knowledge reconstruction;

- a theory of linguistic processing

- a theory of learning.

When I look (yet again!) at Chapter Three of Long’s (2015) book SLA & TBLT, I find that his eloquently described “Cognitive-Interactionist Theory of SLA” relies on carefully selected “Problems and Explanations”. It’s prime concern is “Instructed SLA”, and it revolves around the problem of why most adult L2 learning is “largely unsuccessful”. It’s not an attempt to construct a full theory of SLA, and I’m quite sure that Long knew exactly what he was doing when he confined himself to articulating his four problems and eight explanations. Maybe this also explains Mike’s comment in the recent post here:

I side with Nick Ellis and the UB (not UG) hordes. Since learning a new language is far too large and too complex a task to be handled explicitly, and although it requires more input and time, implicit learning remains the default learning mechanism for adults.

This looks to me like a good indication of the way things are going.

“Do you fancy a bit more wine?” my wife asks, proffering a bottle of chilled 2019 Viña Esmeralda (a cheeky, very fruity wine; always get the most recent year). “Is the Pope a Catholic?” says I, wishing I had Neil McMillan’s ready ability to come up with a more amusing quote from Pynchon.

References

Carroll, S. (1997) Putting ‘input’ in its proper place. Second Language Research 15,4; pp. 337–388.

Carroll, S. (2001) Input and Evidence. Amsterdam, Bejamins.

Gass, S. (1997) Input, Interaction and the Second Language Learner. Marwash, N. J. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gregg, K. R. (1984) Krashen’s monitor and Occam’s razor. Applied Linguistics 5, 79-100.

Krashen, S. (1985) The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. New York: Longman.

Long, M. H. (2015). Second language acquisition and Task-Based Language Teaching. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

McLaughlin, B. (1987) Theories of Second Language Learning. London: Edward Arnold.

Schmidt, R. (1990) The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics 11, 129-58.

Schmidt, R. (2001) Attention. In Robinson, P. (ed.) Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 3-32.

Sharwood Smith, M., & Truscott, J. (2014). The Multilingual Mind. In The Multilingual Mind: A Modular Processing Perspective . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tomlin, R., & Villa, H. (1994). Attention in cognitive science and second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 16, 183-203.

Pingback: Smith and Conti on Memory and SLA | What do you think you're doing?