Developing a transition theory

What is the process of SLA? How do people get from no knowledge of the L2 to some level of proficiency? Before going on, I should make it clear that I’m only looking at psycholinguistic theories, thus ignoring important social aspects of L2 learning and, even within the realm of cognition, leaving out such factors as aptitude and motivation.

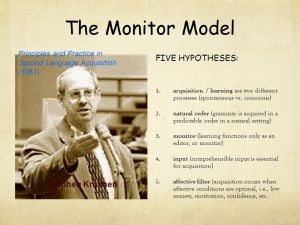

Krashen’s Monitor Model

Krashen’s (1977a, 1977b, 1978, 1981, 1982, 1985) Monitor Model came hard on the heels of Corder’s work, and contains the following five hypotheses:

The Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis.

Adults have two ways of developing L2 competence:

- via acquisition, that is, picking up a language naturally, more or less like children do their L1, by using language for communication. This is a subconscious process and the resulting acquired competence is also subconscious.

- via language learning, which is a conscious process and results in formal knowledge of the language.

For Krashen, the two knowledge systems are separate.”Acquired” knowledge is what explains communicative competence. Knowledge gained through “learning” can’t be internalised and thus serves only the very minor role of acting as a monitor of the acquired system, checking the correctness of utterances against the formal knowledge stored therein.

The Natural Order Hypothesis

The rules of language are acquired in a predictable way, some rules coming early and others late. The order is not determined solely by formal simplicity, and it is independent of the order in which rules are taught in language classes.

The Monitor Hypothesis

The learned system has only one, limited, function: to act as a Monitor. Further, the Monitor cannot be used unless three conditions are met:

- Enough time. “In order to think about and use conscious rules effectively, a second language performer needs to have sufficient time” (Krashen, 1982:12).

- Focused on form “The performer must also be focused on form, or thinking about correctness” (Krashen, 1982: 12).

- Knowledge of the rule.

The Input Hypothesis

Second languages are acquired by understanding language that contains structure “a bit beyond our current level of competence (i + 1) by receiving “comprehensible input”. “When the input is understood and there is enough of it, i + 1 will be provided automatically. Production ability emerges. It is not taught directly” (Krashen, 1982: 21-22).

The Affective Filter Hypothesis

The Affective Filter is “that part of the internal processing system that subconsciously screens incoming language based on … the learner’s motives, needs, attitudes, and emotional states” (Dulay, Burt, and Krashen, 1982: 46). If the affective Filter is high, (because of lack of motivation, or dislike of the L2 culture, or feelings of inadequacy, for example) input is prevented from passing through and hence there is no acquisition. The Affective Filter is responsible for individual variation in SLA (it is not something children use) and explains why some learners never acquire full competence.

Discussion

The biggest problem with Krashen’s account is thatThere is no way of testing the Acquisition-Learning hypothesis: we are given no evidence to support the claim that two distinct systems exist, nor any means of determining whether they are, or are not, separate. Similarly, there is no way of testing the Monitor hypothesis: with no way to determine whether the Monitor is in operation or not, it is impossible to determine the validity of its extremely strong claims. The Input Hypothesis is equally mysterious and incapable of being tested: the levels of knowledge are nowhere defined and so it is impossible to know whether i + 1 is present in input, and, if it is, whether or not the learner moves on to the next level as a result. Thus, the first three hypotheses make up a circular and vacuous argument. The Monitor accounts for discrepancies in the natural order, the learning-acquisition distinction justifies the use of the Monitor, and so on.

Further, the model lacks explanatory adequacy. At the heart of the model is the Acquisition-Leaning Hypothesis which simply states that L2 competence is picked up through comprehensible input in a staged, systematic way, without giving any explanation of the process by which comprehensible input leads to acquisition. Similarly, we are given no account of how the Affective Filter works, of how input is filtered out by an unmotivated learner.

Finally, Krashen’s use of key terms, such as “acquisition and learning”, and “subconscious and conscious”, is vague, confusing, and, not always consistent.

In summary, while the model is broad in scope and is intuitively appealing, Krashen’s key terms are ill-defined, and circular, so that the set is incoherent. The lack of empirical content in the five hypotheses means that there is no means of testing them. As a theory it has such serious faults that it is not really a theory at all.

And yet, Krashen’s work has had an enormous influence, and in my opinion, rightly so. While the acquisition / learning distinction is badly defined, it is, nevertheless, absolutely crucial to current attempts to explain SLA; all the subsequent work on implicit and explicit learning, knowledge, and instruction starts here, as does the work on interlanguage development. Since the questions of conscious and unconscious learning, and of interlanguage development are the two with the biggest teaching implications, and since I think Krashen was basically right about both issues, I personally see Krashen’s work as of enormous and enduring importance.

Processing Approaches

A) McLaughlin: Automaticity and Restructuring

McLaughlin’s (1987) review of Krashen’s Monitor Model is considered one of the most complete rebuttals offered (but see Gregg, 1984). In an attempt to overcome the problems of finding operational definitions for concepts used to describe and explain the SLA process, McLaughlin went on the argue (1990) that the distinction between conscious and unconscious should be abandoned in favour of clearly-defined empirical concepts. McLaughlin substitutes the use of the conscious /unconscious dichotomy with the distinction between controlled and automatic processing. Controlled processing requires attention, and humans’ capacity for it is limited; automatic processing does not require attention, and takes up little or no processing capacity. So, McLaughlin argues, the L2 learner begins the process of acquisition of a particular aspect of the L2 by relying heavily on controlled processing; then, through practice the learner’s use of that aspect of the L2 becomes automatic.

McLaughlin uses the twin concepts of Automaticity and Restructuring to describe the cognitive processes involved in SLA. Automaticity occurs when an associative connection between a certain kind of input and some output pattern occurs. Many typical greetings exchanges illustrate this:

Speaker 1: Morning.

Speaker 2: Morning. How are you?

Speaker 1: Fine, and you?

Speaker 2: Fine.

Since humans have a limited capacity for processing information, automatic routines free up more time for processing new information. The more information that can be handled automatically, the more attentional resources are freed up for new information. Learning takes place by the transfer of information to long-term memory and is regulated by controlled processes which lay down the stepping stones for automatic processing.

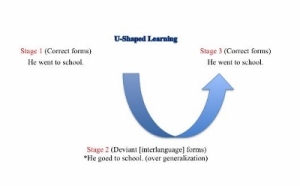

The second concept, restructuring, refers to qualitative changes in the learner’s interlanguage as they move from stage to stage, not to the simple addition of new structural elements. These restructuring changes are, according to McLaughlin, often reflected in “U-shaped behaviour”, which refers to three stages of linguistic use:

- Stage 1: correct utterance,

- Stage 2: deviant utterance,

- Stage 3: correct usage.

In a study of French L1 speakers learning English, Lightbown (1983) found that, when acquiring the English “ing” form, her subjects passed through the three stages of U-shaped behaviour. Lightbown argued that as the learners, who initially were only presented with the present progressive, took on new information – the present simple – they had to adjust their ideas about the “ing” form. For a while they were confused and the use of “ing” became less frequent and less correct. TBelow is a diagram showing the same process for past tense forms:

Discussion

McLaughlin suggested getting rid of the unconscious / conscious distinction because it wasn’t properly defined by Krashen, but in doing so he threw the baby out with the bathwater. Furthermore, we have to ask to what extent the terms “controlled processing” and “automatic processing” are any better; after all, measuring the length of time necessary to perform a given task is a weak type of measure, and one that does little to solve the problem it raises.

Still, the “U-shaped” nature of staged development has been influential in successive attempts to explain interlanguage development, and we may note that McLaughlin was, with Bialystock, among the first scholars to apply general cognitive psychological concepts of computer-based information-processing models to SLA research. Chomsky’s Minimalist Program confirms his commitment to the view that cognition consists in carrying out computations over mental representations. Those adopting a connectionist view, though taking a different view of the mind and how it works, also use the same metaphor. Indeed the basic notion of “input – processing – output” has become an almost unchallenged account of how we think about and react to the world around us. While in my opinion the metaphor can be extremely useful, it is worth making the obvious point that we are not computers. One may well sympathise with Foucault and others who warn us of the blinding power of such metaphors.

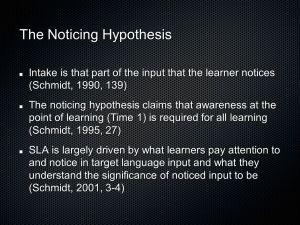

Schmidt’s noticing hypothesis

Rather than accept McLaughlin’s advice to abandon the search for a definition of “consciousness”, Schmidt attempts to do away with its “terminological vagueness” by examining it in detail. His work has proved enormously influential, but I think there are serious problems with the “Noticing Hypothesis”, and that is has been widely misinterpreted in order to justify types of explicit instruction that are not actually supported by a more considered view of the evidence. I’ll deal with this in Part 4.

See Bibliography in Header for all references