This blog is dedicated to improving the quality of Second Language Teacher Education (SLTE)

The Teacher Trainers and Educators

The most influential ELT teacher trainers and educators are those who publish “How to teach” books and articles, have on-line blogs and a big presence on social media, give presentations at ELT conferences, and travel around the world giving workshops and teacher training & development courses. Many of the best known and highest paid teacher educators are also the authors of coursebooks. Apart from the top “influencers”, there are tens of thousands of teacher trainers worldwide who deliver pre-service courses such as CELTA, or the Trinity Cert TESOL, or an MA in TESOL, and thousands working with practicing teachers in courses such as DELTA and MA programmes. Special Interest Groups in TESOL and IATEFL also have considerable influence.

What’s the problem?

Most current SLTE pays too little attention to the question “What are we doing?”, and the follow-up question “Is what we’re doing effective?”. The assumption that students will learn what they’re taught is left unchallenged, and those delivering SLTE concentrate either on coping with the trials and tribulations of being a language teacher (keeping fresh, avoiding burn-out, growing professionally and personally) or on improving classroom practice. As to the latter, they look at new ways to present grammar structures and vocabulary, better ways to check comprehension of what’s been presented, more imaginative ways to use the whiteboard to summarise it, more engaging activities to practice it, and the use of technology to enhance it all, or do it online. A good example of this is Adrian Underhill and Jim Scrivener’s “Demand High” project, which leaves unquestioned the well-established framework for ELT and concentrates on doing the same things better. In all this, those responsible for SLTE simply assume that current ELT practice efficiently facilitates language learning. But does it? Does the present model of ELT actually deliver the goods, and is making small, incremental changes to it the best way to bring about improvements? To put it another way, is current ELT practice efficacious, and is current SLTE leading to significant improvement? Are teachers making the most effective use of their time? Are they maximising their students’ chances of reaching their goals?

As Bill VanPatten argues in his plenary at the BAAL 2018 conference, language teaching can only be effective if it comes from an understanding of how people learn languages. In 1967, Pit Corder was the first to suggest that the only way to make progress in language teaching is to start from knowledge about how people actually learn languages. Then, in 1972, Larry Selinker suggested that instruction on formal properties of language has a negligible impact (if any) on real development in the learner. Next, in 1983, Mike Long raised the issue again of whether instruction on formal properties of language made a difference in acquisition. Since these important publications, hundreds of empirical studies have been published on everything from the effects of instruction to the effects of error correction and feedback. This research in turn has resulted in meta-analyses and overviews that can be used to measure the impact of instruction on SLA. All the research indicates that the current, deeply entrenched approach to ELT, where most classroom time is dedicated to explicit instruction, vastly over-estimates the efficacy of such instruction.

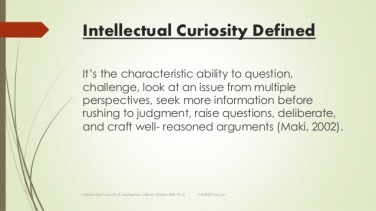

So in order to answer the question “Is what we’re doing effective?”, we need to periodically re-visit questions about how people learn languages. Most teachers are aware that we learn our first language/s unconsciously and that explicit learning about the language plays a minor role, but they don’t know much about how people learn an L2. In particular, few teachers know that the consensus of opinion among SLA scholars is that implicit learning through using the target language for relevant, communicative purposes is far more important than explicit instruction about the language. Here are just 4 examples from the literature:

1. Doughty, (2003) concludes her chapter on instructed SLA by saying:

In sum, the findings of a pervasive implicit mode of learning, and the limited role of explicit learning in improving performance in complex control tasks, point to a default mode for SLA that is fundamentally implicit, and to the need to avoid declarative knowledge when designing L2 pedagogical procedures.

2. Nick Ellis (2005) says:

the bulk of language acquisition is implicit learning from usage. Most knowledge is tacit knowledge; most learning is implicit; the vast majority of our cognitive processing is unconscious.

3. Whong, Gil and Marsden’s (2014) review of a wide body of studies in SLA concludes:

“Implicit learning is more basic and more important than explicit learning, and superior. Access to implicit knowledge is automatic and fast, and is what underlies listening comprehension, spontaneous speech, and fluency. It is the result of deeper processing and is more durable as a result, and it obviates the need for explicit knowledge, freeing up attentional resources for a speaker to focus on message content”.

4. ZhaoHong, H. and Nassaji, H. (2018) review 35 years of instructed SLA research, and, citing the latest meta-analysis, they say:

On the relative effectiveness of explicit vs. implicit instruction, Kang et al. reported no significant difference in short-term effects but a significant difference in longer-term effects with implicit instruction outperforming explicit instruction.

Despite lots of other disagreements among themselves, the vast majority of SLA scholars agree on this crucial matter. The evidence from research into instructed SLA gives massive support to the claim that concentrating on activities which help implicit knowledge (by developing the learners’ ability to make meaning in the L2, through exposure to comprehensible input, participation in discourse, and implicit or explicit feedback) leads to far greater gains in interlanguage development than concentrating on the presentation and practice of pre-selected bits and pieces of language.

One of the reasons why so many teachers are unaware of the crucial importance of implicit learning is that so few of those responsible for SLTE talk about it. Teacher trainers and educators don’t tell pre-service or practicing teachers about the research findings on interlanguage development, or that language learning is not a matter of assimilating knowledge bit by bit; or that the characteristics of working memory constrain rote learning; or that by varying different factors in tasks we can significantly affect the outcomes. And there’s a great deal more we know about language learning that those responsible for SLTE don’t pass on to teachers, even though it has important implications for everything in ELT from syllabus design to the use of the whiteboard; from methodological principles to the use of IT, from materials design to assessment.

We know that in the not so distant past, generations of school children learnt foreign languages for 7 or 8 years, and the vast majority of them left school without the ability to maintain an elementary conversational exchange in the L2. Only to the extent that teachers have been informed about, and encouraged to critically evaluate, what we know about language learning, constantly experimenting with different ways of engaging their students in communicative activities, have things improved. To the extent that teachers continue to spend most of the time talking to their students about the language, those improvements have been minimal. So why is all this knowledge not properly disseminated?

Most teacher trainers and educators, including Penny Ur (see below), say that, whatever its faults, coursebook-driven ELT is practical, and that alternatives such as TBLT are not. Ur actually goes as far as to say that there’s no research evidence to support the view that TBLT is a viable alternative to coursebooks. Such an assertion is contradicted by the evidence. In a recent statistical meta-analysis by Bryfonski & McKay (2017) of 52 evaluations of program-level implementations of TBLT in real classroom settings, “results revealed an overall positive and strong effect (d = 0.93) for TBLT implementation on a variety of learning outcomes” in a variety of settings, including parts of the Middle-East and East Asia, where many have flatly stated that TBLT could never work for “cultural” reasons, and “three-hours-a-week” primary and secondary foreign language settings, where the same opinion is widely voiced. So there are alternatives to the coursebook approach, but teacher trainers too often dismiss them out of hand, or simply ignore them.

How many SLTE courses today include a sizeable component devoted to the subject of language learning, where different theories are properly discussed so as to reveal the methodological principles that inform teaching practice? Or, more bluntly: how many such courses give serious attention to examining the complex nature of language learning, which is likely to lead teachers to seriously question the efficacy of basing teaching on the presentation and practice of a succession of bits of language? Current SLTE doesn’t encourage teachers to take a critical view of what they’re doing, or to base their teaching on what we know about how people learn an L2. Too many teacher trainers and educators base their approach to ELT on personal experience, and on the prevalent “received wisdom” about what and how to teach. For thirty years now, ELT orthodoxy has required teachers to use a coursebook to guide students through a “General English” course which implements a grammar-based, synthetic syllabus through a PPP methodology. During these courses, a great deal of time is taken up by the teacher talking about the language, and much of the rest of the time is devoted to activities which are supposed to develop “the 4 skills”, often in isolation. There is good reason to think that this is a hopelessly inefficient way to teach English as an L2, and yet, it goes virtually unchallenged.

Complacency

The published work of most of the influential teacher educators demonstrates a poor grasp of what’s involved in language learning, and little appetite to discuss it. Penny Ur is a good example. In her books on how to teach English as an L2, Ur spends very little time discussing the question of how people learn an L2, or encouraging teachers to critically evaluate the theoretical assumptions which underpin her practical teaching tips. The latest edition of Ur’s widely recommended A Course in Language Teaching includes a new sub-section where precisely half a page is devoted to theories of SLA. For the rest of the 300 pages, Ur expects readers to take her word for it when she says, as if she knew, that the findings of applied linguistics research have very limited relevance to teachers’ jobs. Nowhere in any of her books, articles or presentations does Ur attempt to seriously describe and evaluate evidence and arguments from academics whose work challenges her approach, and nowhere does she encourage teachers to do so. How can we expect teachers to be well-informed, critically acute professionals in the world of education if their training is restricted to instruction in classroom skills, and their on-going professional development gives them no opportunities to consider theories of language, theories of language learning, and theories of teaching and education? Teaching English as an L2 is more art than science; there’s no “best way”, no “magic bullet”, no “one size fits all”. But while there’s still so much more to discover, we now know enough about the psychological process of language learning to know that some types of teaching are very unlikely to help, and that other types are more likely to do so. Teacher educators have a duty to know about this stuff and to discuss it with thier trainees.

Scholarly Criticism? Where?

Reading the published work of leading teacher educators in ELT is a depressing affair; few texts used for the purpose of teacher education in school or adult education demonstrate such poor scholarship as that found in Harmer’s The Practice of Language Teaching, Ur’s A Course in Language Teaching, or Dellar and Walkley’s Teaching Lexically, for example. Why are these books so widely recommended? Where is the critical evaluation of them? Why does nobody complain about the poor argumentation and the lack of attention to research findings which affect ELT? Alas, these books typify the general “practical” nature of SLTE, and their reluctance to engage in any kind of critical reflection on theory and practice. Go through the recommended reading for most SLTE courses and you’ll find few texts informed by scholarly criticism. Look at the content of SLTE courses and you’ll be hard pushed to find a course which includes a component devoted to a critical evaluation of research findings on language learning and ELT classroom practice.

There is a general “craft” culture in ELT which rather frowns on scholarship and seeks to promote the view that teachers have little to learn from academics. Those who deliver SLTE are, in my opinion, partly responsible for this culture. While it’s unreasonable to expect all teachers to be well informed about research findings regarding language learning, syllabus design, assessment, and so on, it is surely entirely reasonable to expect teacher trainers and educators to be so. I suggest that teacher educators have a duty to lead discussions, informed by relevant scholarly texts, which question common sense assumptions about the English language, how people learn languages, how languages are taught, and the aims of education. Furthermore, they should do far more to encourage their trainees to constantly challenge received opinion and orthodox ELT practices. This surely, is the best way to help teachers enjoy their jobs, be more effective, and identify the weaknesses of current ELT practice.

My intention in this blog is to point out the weaknesses I see in the works of some influential ELT teacher trainers and educators, and invite them to respond. They may, of course, respond anywhere they like, in any way they like, but the easier it is for all of us to read what they say and join in the conversation, the better. I hope this will raise awareness of the huge problem currently facing ELT: it is in the hands of those who have more interest in the commercialisation and commodification of education than in improving the real efficacy of ELT. Teacher trainers and educators do little to halt this slide, or to defend the core principles of liberal education which Long so succinctly discusses in Chapter 4 of his book SLA and Task-Based Language Teaching.

The Questions

I invite teacher trainers and educators to answer the following questions:

1 What is your view of the English language? How do you transmit this view to teachers?

2 How do you think people learn an L2? How do you explain language learning to teachers?

3 What types of syllabus do you discuss with teachers? Which type do you recommend to them?

4 What materials do you recommend?

5 What methodological principles do you discuss with teachers? Which do you recommend to them?

References

Bryfonski, L., & McKay, T. H. (2017). TBLT implementation and evaluation: A meta-analysis. Language Teaching Research.

Dellar, H. and Walkley, A. (2016) Teaching Lexically. Delata.

Doughty, C. (2003) Instructed SLA. In Doughty, C. & Long, M. Handbook of SLA, pp 256 – 310. New York, Blackwell.

Long, M. (2015) Second Language Acquisition and Task-Based Language Teaching. Oxford, Wiley.

Ur, P. A Course in Language Teaching. Cambridge, CUP.

Whong, M., Gil, K.H. and Marsden, H., (2014). Beyond paradigm: The ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of classroom research. Second Language Research, 30(4), pp.551-568.

ZhaoHong, H. and Nassaji, H. (2018) Introduction: A snapshot of thirty-five years of instructed second language acquisition. Language Teaching Research, in press.

Hi Geoff!

This comment doesn’t exactly answer all of your questions in order, I’m afraid, but is rather a collection of thoughts I had while reading your post.

I work within a programme that trains secondary-school EFL teachers here in Germany. I have the impression that the training future language teachers receive often differs quite significantly depending on whether they’re being trained / aiming to qualify as teachers in the state sector or the private sector. I wonder whether many of the issues you raise with teacher training are more problematic in the private sector?

In my experience in Western Europe, state-school language teachers usually have a degree in the language (or any other subject) they teach and a couple of years studying pedagogy. (Though I admit I’m not an expert on countries beyond this region, so perhaps the private / state dichotomy is not the root of the problems elsewhere!). Where I work, for example, students enrol on B.Ed. and M.Ed. degrees, where they study the subject they will later teach alongside Educational Sciences and subject-specific didactics. They need to complete an M.Ed. to be allowed to proceed to the practical training part (18 months) of their state teaching qualification. Completing a B.Ed. followed by an M.Ed. means they study for at least 5 years, which allows ample time for deeper discussions of learning theory, evaluations of syllabus types, and engagement with current SLA and psychology research, for example. Modules offered here include ‘Applied Linguistics and Language Teaching’, ‘Theories of Teaching, Learning and Motivation’, ‘Child Development and Education’ and ‘Understanding Knowledge and Ability: Second Language Learning’ (some titles translated). Of course, I have not sat through or taught all of these modules, but from the descriptions, I believe that they cover many of the areas you feel are missing in much language-teacher training.

This is what makes me think that one root of the issues you discuss in your post is the training often offered for language teachers in the private sector. As far as I’m aware, most language schools and similar do not require a master’s degree like the one I describe above. Often, a certificate from an intensive training programme (and often being a NS, but that’s a discussion for another day!) is seen as ‘good enough’. (Again, a discussion for another day!) Intensive teacher training programmes that run just for a number of weeks or months clearly do not have the luxury of being able to spend as much time on understanding the links between SLA research and teaching methodologies as a 5-year degree programme. This does not mean they should be allowed to ignore SLA research insights, but need to find alternative workarounds for exposing future teachers to this information. I would agree with you in expecting at least the trainers to have an in-depth understanding of language-learning mechanisms, though I wouldn’t want to claim that this is never the case. They could then provide their trainees with recommendations for extra reading, for example; ideally resources that summarise SLA research findings in an accessible manner and use these to explain or justify suggested teaching techniques. I’m sure there are books like this on the market.

In general, to ease some of the issues you have discussed in your post, I guess really what we need are more, practical suggestions of ways to impart this understanding within short-term training programmes – in my view, that would be where the biggest difficulties occur.

Hi Clare,

Thanks very much for taking the time to address the issues I’ve raised here.

I agree 100% that what we need are more practical suggestions of ways to impart an understanding of language learning within short-term training programmes – and that these are the most difficult programmes to change. But it’s surely not impossible. At least trainee teachers could be told about what makes language learning special, why using the target language is so important, and why talking about it has limited results.

Thanks again.

What is your view of the English language? How do you transmit this view to teachers?

I’m not 100% sure what this question means, but my first idea was that English is a vast living breathing exciting thing that I’m always learning more about.

How do you think people learn an L2? How do you explain language learning to teachers?

Practice. In my teaching context students have just finished standardized tests with no speaking component and haven’t practiced that very much at all, so I get them to speak for as much of the class as possible. I guess this means I don’t believe people learn an L2 through input only.

What types of syllabus do you discuss with teachers? Which type do you recommend to them?

I work at a university, so we have to have a fairly standardized one. At the moment we’re pushing towards a syllabus that’s more activity/TBLT centered than lecture centered. This is quite different to what students and some of our coworkers are used to, so we’re pushing gently.

What materials do you recommend?

Conversation Strategies by Kehe and Kehe is probably one of my favorites for getting students talking.

What methodological principles do you discuss with teachers? Which do you recommend to them?

I’m not sure we do discuss this kind of thing that often. We’ll often talk about specific classes and what worked, what didn’t and what could have done differently. I think most teachers don’t talk about methodological principles as much as they talk about specific methods; I’m not sure that’s a bad thing as I think the methods are far more relevant to their actual teaching.

Hi Timothy,

Thanks very much for your replies. I wish you the best with your gentle pushing towards a more activity/TBLT centered syllabus.

Hello Geoff,

My thought after reading this post is that the problem is more practical than theoretical.

In my experience, the theoretical background given to language teachers in professional development (for example, in the CELTA YL extension) is very much in line with your position, which reflects a substantial consensus in academia. The problem is not the background theory but the availability of ways of implementing it. Teachers are faced with the choice of basing lesson plans on a coursebook or trying to create 20-30 hours of lessons from scratch with only general guidance from textbooks on methods such as TBL. I have taught in a centre where the AM and both Senior Teachers supported TBL in principle but rarely, if ever, actually used it, being managers as well as teachers and having to plan lessons with their left foot just to fit everything in to a 12-hour working day.

My view of the situation is that English teachers with a couple of years experience and some history of professional development know what approach they should ideally be using; they are lacking practical and accessible ways of putting it into practice.

Hi Michael,

Thanks for your comment.

Scott Thornbury’s report on what 4 well-known teacher trainers told him, plus the evidence from teacher trainers’ blogs and books and conference presentations, all suggests that teacher training in ELT does not give much time to a critical evaluation of research findings in SLA, or to syllabus design, or to questioning coursebook-driven ELT.

I appreciate the practical problems involved in organising an alternative approach to ELT such as TBLT, but they’re not insurmountable, as many schools and cooperatives have shown. “Where there’s a will….” and all that. Change has an initial cost, of course, but those who apppreciate just how bad coursebook-driven ELT is, and how rewarding alternatives can be, are often willing to invest in change.

There’s a huge commercial juggernaut supporting coursebook-driven ELT. Alternatives are not given a fair hearing, the difficulties are exaggerated, and everybody’s encouraged to tow the line. Which is why I’m afraid I don’t share your view of the situation, I’m afraid; but thanks very much for taking the time to comment.

Hello Geoff

I agree with the principles of TBLT (and am also a fan of the 2015 Mike Long tome.) It’s not the most “trainable” format for initial TT in that trainees have really to know their stuff about language to do the FonF well, and this is generally something that comes with experience.

I do demo and offer a “lite” version which I call Task-Teach-Task, which is something like the well-known test-teach-test lesson shape, except that the diagnostic test and the controlled practice are both more open communicative tasks. It can work well with stronger trainees. I know that there are TBL-based CELTAs out there, and also CELTA courses where the students (rather than coursebooks) drive the curriculum.

I wonder if you could help me. I am doing a talk called Where is TBLT Now and I wondered if you had any articles about where/how the method is used. I don’t hear much talk about it in the ELT world, though many people are aware that it’s supported by findings in SLA research.

Hi Neil,

Thanks for your comments.

In answer to your question, I recommend

Bryfonski,L. and McKay,T. (2017) TBLT implementation & evaluation: A meta-analysis” LTR, December.

If you can’t get access to it, email me.

Thank you. I’ll look at that.

My main point, which I think is important, is that on pre-service training courses, the candidates lack the expertise in language that would allow the to focus on language forms, without these forms being pre-selected and prepared. So the kind of TBLT that we can offer is a bastardised version. The demand for teachers appears to be vast – so most of them develop expertise as they go, and don’t really try out TBLT until Diploma level. I can’t think of an easy way round this problem.

Hi Nick,

I take the point. Experience is surely the key to the tricky business of deciding when and how to give more punctual, more nuanced “focus on form”, rather than just following the coursebook presentation of the past tense, for example.

But, IMHO, this doesn’t justify the fact that CELTA and other training courses encourage a coursebook-driven, PPP model of ELT which flies in the face of robust research findings. Surely teachers should begin their training by looking at the special way that people learn languages, because the special nature of language learning constrains students’ ability to learn what they’re taught.

“This is what we know about how people learn an L2” should be the first 15% of the course. The rest of the course could look at

1. Appproaches to ELT that take a holistic view of language and that concentrate on relevant communicative practice,

2. The English language – special attention to lexical chunks

3. Classroom management

4. Syllabus design.

not necessarily in that order. Of course, the reality of coursebook-driven ELT would have to be faced, but there’s no need to completely capitulate to it right from the start.

I agree. At the moment, all this appears on Diploma-level courses. The certificate has always been (in theory) “just” a licence to teach. DELTA or Dip TESOL is the full qualification, and both include an introduction to SLA.

Pingback: The learning process as I see it | Sandy Millin

Dear Geoff,

I hope this blogpost goes some way towards answering your questions: https://wp.me/p18yiK-1Jt

In response to your previous reply to Neil about course structure, I would be very interested to see a sample timetable showing what sessions you would include on a pre-service course that would give teachers the type of grounding in theory you advocate coupled with the practical advice we currently aim to give them. On a typical CELTA course, you would probably have an absolute maximum of 40 x 75-minute sessions to play with, 2 per day/10 per week. However this is more normally around 32-35, once you have taken out time for tutorials in weeks 1 and 2, the assessor’s visit in week 3/4, one or two ‘free’ sessions for assignment writing, etc.

Thank you,

Sandy

Dear Sandy,

Thanks very much fr this comment and for taking the time to write such a full, interesting post on your blog in answer to the questions I posed.

I’ll suggest a timetable for sessions in a pre-service course soon.

Best,

Geoff

Pingback: ELT WTF 1.04 Michael Griffin on Social Media and Teacher Development –

Hi Geoff,

There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root. I am sincere in saying how grateful I am to you for your persistence and clarity about something that I feel very strongly about.

I can’t as yet answer the questions from practical experience I’m afraid, as I am currently working on my own practice first, but do intend to train (and employ) teachers in the very near future.

What I see is an ELT Leviathan of publishers, writers, designers, trainers and examining boards striding forward day by day and making real progress, impressive progress. I’m overwhelmed sometimes by the distance travelled in such a short period of time. But the fact remains that all that progress and influence amounts to nothing if you are going in the wrong direction. It’s not a question of doing things right, but doing the right thing.

My own take, when I start teacher training, will be to install on the participants a deep respect for the complexities and workings of the human mind, an awe for the creative process of meaning making and a belief that the driving force behind language learning is the need to communicate, to connect and to be understood. We learn from the many to the one, not the one (grammar rule) to the many. Our brains are massive storage devices of experiences rather than real time processors.

In short, my teachers will be trained in structuring communication, giving feedback on what’s good and what’s bad, then advising on the next steps to improve upon performance. That’s the plan anyway 🙂

Hi Mark,

Many thanks for you kind comments. I wish you all the best with your venture and let’s hope your plan works. We can only try!

Hi Geoff… it’s taken me 4 months to get round to it but here are some hastily written thoughts:

1.What is your view of the English language?

A useful tool for international communication.

2.How do you think people learn an L2? How do you explain language learning to teachers?

Practice, practice, practice, corrective feedback, more practice, bit of input (some people bloody love rules and formulas), more practice. Awareness. Did I mention practice?

What types of syllabus do you discuss with teachers? Which type do you recommend to them?

I talk constantly about needs analysis and making things relevant to learners. Choice of syllabus should depend entirely on that.

4.What materials do you recommend?

I recommend a lot of books and resources for the trainees to develop their knowledge and skills, far fewer for them to use with students. I give input sessions on using authentic materials with learners and emphasise that the learners are their best resource.

5.What methodological principles do you discuss with teachers? Which do you recommend to them?

Is it awful that it’s not completely clear what you mean by methodological principles? I tell trainees about classic lesson shapes – PPP, TTT, TBL, Dogme; process writing, a product approach, decoding and developing bottom up listening skills as well as top down…. we discuss the pros and cons of each; ultimately it comes down to deciding what best suits the learners in front of them. that’s my main message.

As I work on very short training courses, a lot of what I’m focusing on is practical stuff: giving clear and useful instructions, giving feedback on tasks, recording emergent language on the board in the most useful way (highlighting salient phonological features, word class, co-text, collocations etc.) building rapport with students, correcting sensitively but usefully, monitoring appropriately etc.

I am well aware of the short comings of the CELTA course for all the reasons you often mention. My view is that people will go off and “teach English” regardless of whether they are qualified or not, and the CELTA, or at least the CELTAs I work on, are better than nothing. The progress that trainees can make in 4 weeks can be impressive, and they leave with a better understanding of the English language, some teaching skills that will be of real value, and an understanding of the importance, I hope, of teaching the students in front of them, rather than teaching the plan/the book etc.

Hi Amy,

Thanks very much for this; much appreciated.

Of course I agree: “practice, practice, practice”! And I take you to mean: devote most of classroom time to giving students opportunites to practice using the target language to talk about stuff that’s relevant to their needs. Giving students opportunities to practice the L2 is more important than telling them about the L2. Right? I hope I’m not putting words in your mouth.

As for CELTA, it is, of course, better than nothing, but why can’t it focus more on giving students time to practice, and less on jumping thru all the boring hoops you find in coursebooks?

Thanks again.

No, not putting words into my mouth; that is indeed what I meant, and what I pass on to trainees.

I’d say [the CELTA courses I work on] DO focus on giving students time to practice. Which boring hoops are you talking about? The trainees have to jump through some, but they are mostly useful; to help them develop their awareness, reflect on their teaching, to show that they can analyse language etc. as this is useful for answering students’ questions when focusing on form, helping them notice patterns and tendencies etc.

I certainly don’t ask trainees to get students to jump through stupid hoops (though it’s amazing what you see some trainees ask students to do… can they hear themselves?!) in fact, that’s the sort of thing that CELTA can stop, as we have a chance to observe them and give useful feedback (e.g. please don’t ask students to read weird decontextualised sentences aloud, it’s meaningless and they would never do this in real life, give them a task that’s meaningful and relevant to them, etc.)

P.S. 2. “Neuroscience should be required for all students [of education] . . . to familiarize them with the orienting concepts [of] the field, the culture of scientific inquiry, and the special demands of what qualifies as scientifically based education research.” – Eisenhart & DeHaan, 2005

I can understand your frustration with other teacher educators who don’t agree with you on the importance of presenting and discussing the findings of SLA research, but I see a parallel between the fallacy of teaching learners about language rather than letting them learn implicitly by using the language and the probable fallacy of trying to teach EFL influencers to change their ways by explicit instruction rather than letting them discover the benefits of implicit learning.

But then, how can you possibly make that happen? It reminds me of the old joke about how many SLA scholars does it take to change an ELT expert? It all depends on whether the ELT expert wants to be changed. And the answer is, they don’t.

You mention in passing that much of ELT teaching is simply a slight adaptation of the way teachers themselves learnt, or more likely, were taught languages when they were young.

It’s a chicken and egg situation without the benefits of evolution. Until there are ELT experts who have learnt languages themselves implicitly in a classroom context, there won’t be ELT influencers pushing for the adoption of ways for teachers to help learners to learn languages implicitly in schools.

My comments are 5 years late! But then this popst of yours was at the top of your blog and I didn’t notice the date until later. Anyway, better late….

Pingback: Review: English Language Teaching Now and How It Could Be – Geoff Jordan and Mike Long – SPONGE ELT