Nothing in 2023 compares to Israel’s response to the Hamas-led attack of October 7th. As of today, according to Euro-Med Monitor, 85% of the population of Gaza (2,2 million) have been displaced, and the total number of Palestinian deaths in the Gaza Strip since 7 October is 21,731, including 8,697 children and 4,410 women as well as those missing and trapped under the rubble who are now presumed dead. Israel has increased the shocking extent of its targeting of civilians since the humanitarian truce collapsed, intensifying its complete destruction of residential areas and targeting schools that house thousands of displaced individuals in an apparent effort to increase the number of civilian victims. On a never-before-seen scale, Israel’s extensive bombing campaign has targeted both displaced civilians and civilian infrastructure, including hospitals, UN-run schools, mosques, churches, bakeries, water tanks, and even ambulances. On average, one child is killed and two are injured every 10 minutes during the war, turning Gaza into a “graveyard for children,” according to the UN Secretary-General. Almost 200 medics, 102 UN staff, 41 journalists, frontline and human rights defenders, have also been killed, while dozens of families over five generations have been wiped out.

“This occurs amidst Israel’s tightening of its 16-year unlawful blockade of Gaza, which has prevented people from escaping and left them without food, water, medicine and fuel for weeks now, despite international appeals to provide access for critical humanitarian aid. As we previously said, intentional starvation amounts to a war crime,” a team of UN experts wrote in a recent communique. They noted that half of the civilian infrastructure in Gaza has been destroyed, as well as hospitals, schools, mosques, bakeries, water pipes, sewage and electricity networks, in a way that threatens to make the continuation of Palestinian life in Gaza impossible. “The reality in Gaza, with its unbearable pain and trauma on the survivors, is a catastrophe of enormous proportions,” the experts said.

We must keep pressing for an immediate ceasefire and humanitarian aid. While the Gaza genocide continues, it feels trivial to discuss what’s happened this year in ELT, but here’s my personal take on how the year’s gone.

Evan Frendo: “English for the Workplace”

For me, the best event of 2023 was Evan Frendo’s Plenary, “English for the Workplace” at the IATEFL, 2023 conference. I did a post on it, based on Sandy Millin’s excellent notes (click the highlighted text above to see the post, which includes the video recording of Frendo’s talk), where I suggested that Frendo’s approach to ELT is revolutionary.

One of Frendo’s jobs is to help those who work in Vessel traffic service – the water equivalent of air traffic control. He used this example of “English for the workplace” to describe how he addressed the English needs of workers. What’s so revolutionary is that Frendo – and many of his colleagues – reject just about everything that typifies current ELT practice, at least as represented by IATEFL.

In Frendo’s world of “English for the Workplace”, they focus on “doing things in English”. Getting high marks in tests like IELTS has no place here, and neither do coursebooks. Standard English is replaced in practice by BELF: English as a business language Franca. As Frendo said:

“Conformity with standard English is seen as a fairly irrelevant concept. …. I don’t actually care whether something is correct or incorrect. As long as the meaning is not distorted. … BELF is perceived as an enabling resource to get the work done. Since it is highly context-bound and situation-specific, it is a moving target defying detailed linguistic description.”

Furthermore, the current CEFR idea of proficiency is challenged. In VTS communication, assessment is carried out by a team consisting of:

- English teacher

- Experienced VTS operator – say whether they’ve done the right thing

- Legal expert- all conversations are recorded, but they can have legal implications

The test criterion is: Can the worker do the job? This chimes perfectly with what we, the advocates of TBLT, suggest.

Here’s the final slide:

Please have a look at my post and click the link to watch Frendo’s extremely well delivered plenary. It’s fantastic and it speaks of the future!

I see that Evan Frendo is a plenary speaker at TESOL Spain’s 2004 conference in March, 2024. As with IATEFL, I can’t believe that the TESOL organisation, which is so dominated by commercial interests, is giving the big stage to this eloquent critic of TESOL’s view of ELT. Never mind – let’s hear it for Evan!

ChatGPT (“generative, pre-trained transformer”)

The best laugh I had about all this was with Neil McMillan when he told me at a jolly restaurant dinner about his run-in with ChatGPT4 (he was probably using ChatGPX11Iaqz or something else I know nothing about) over a game of chess. Neil quickly reduced his opponent to gibbering apologies. “You said you knew the Scillian Defence”, says Neil after ChatGPT, playing White, made a beginner-like blunder. “I obviously have much to learn” says the robot. Three moves later Neil says “Now you’re in a right mess; it’s mate in two.” His opponent blurts out more apologies doing a good imitation of a cringing fraudster: “I do not have enough information; this is unlike the model …..”, and all that.

It’s still relatively easy to make a fool of any program that claims to understand the input they’re given, but obviously, AI is getting better very fast, and it’s going to have a big effect on how we do “education”. There are lots of ways this will play out, but let’s remind ourselves that in language learning, AI is up against one of its toughest problems, because language learning is uniquely complex. This raises the, for me anyway, still unresolved question of whether language learning is a process which is bootstrapped by a particular innate ability for language learning, as Chomsky suggests, or simply a process of using basic, low-level reasoning to use a massively redundant number of linguistic chunks / constructions.

I haven’t kept up with all that’s being done with ChatGPT, but I got off to a good start in February by attending a webinar led by Scott Thornbury where Sam Gravell and Svetlana Kandybovich gave us their well-informed opinions. I recommend it, and I’ve found following Sam Gravell on Linkedin very interesting and informative.

How to teach grammar

The most interesting book on ELT I’ve read this year is Ionin & Montril’s (2023) Second Language Acquisition: Introducing Intervention Research. It sets out to show how grammatical phenomena can best be taught to second language and bilingual learners by “bringing together second language research, linguistics, pedagogical grammar, and language teaching”. The authors assume a generative approach to language and language learning, and use intervention research methods to determine what kinds of pedagogic procedures are most efficacious. The first chapter gives a refreshingly clear discussion of explicit and implicit knowledge, learning and instruction, while Chapter 2 explains intervention research and grammar teaching. The next nine chapters look at how specific linguistic properties (articles, verb placement and question formation, argument structure, word order, ….) are acquired and have been investigated through intervention studies. To quote the authors:

“When we discuss the nature of the intervention, we will address the question of whether it involves primarily explicit or primarily implicit instruction and/or feedback. When we discuss the tests (pretests and posttests) that are used to measure what learners know before and after the intervention, we will note whether the tests are designed to target primarily implicit or primarily explicit knowledge. We will see that some studies manipulate the nature of the instruction as explicit vs. implicit, while others manipulate the tests in order to get measures of both explicit and implicit knowledge. Lichtman (2016) is an example of a study that did both. Many other intervention studies do not set out to manipulate or test the explicit/implicit distinction but are instead concerned with the efficacy of a particular pedagogical method or with applying linguistic theory to classroom research. Nevertheless, even for studies that do not focus on the explicit/implicit divide, it is important to consider whether the knowledge that the learners gain is primarily explicit or implicit, and whether this knowledge resulted from largely explicit or largely implicit instruction”.

Ionin, T., & Montrul, S. (2023). Second Language Acquisition: Introducing Intervention Research. Cambridge University Press.

Translanguaging

In 2023, multilingualism and translanguaging continued to be a hot topics discussed in many assignments done by students enrolled in the University of Leicester’s MA in Applied Linguistics and TESOL, and maybe this reflects not just the sharp increase in the number of articles on these topics appearing in academic journals, but also discussion among teachers and teacher educators in blogs and the social media in general.

Both multilingualism and translanguaging begin with a questioning of how we define language; in particular, they question the assumption that to learn an additional language is to learn a separate, different “system”, comprising of a separate grammar, vocabulary and so on. They suggest that the “traditional approach” to language conceives of bi/multilingualism as the addition of parallel monolingualisms, and regards the hybrid uses of languages by bilinguals as signs of deviant or deficient language knowledge and use. Moving away from such traditional views, translanguaging theorists embrace Bakhtin’s view that “language is inextricably bound to the context in which it exists and is incapable of neutrality because it emerges from the actions of speakers with certain perspectives and ideological positions”. The move from a view of language as a discrete system to ‘languaging’ as a socially situated action is further developed by the construct of “translanguaging” (see, for example, Garcia & Wei (2014). Translanguaging scholarship began with an analysis of the historic conflict between English and Welsh in Wales; English being the dominant language imposed on Wales by English colonial rule, and Welsh being the indigenous language endangered by the colonial language policy which excluded Welsh from formal education spaces in Wales. It has since been expanded theoretically and practically by linguists and educators globally. Two facets stand out. First, García’s “dynamic bilingualism” (which emerges from her distinction between subtractive and additive bilingualism) insists that bilinguals choose parts from a complex linguistic repertoire depending on contextual, topical, and interactional factors. Translanguaging moves beyond languaging by affirming bilinguals’ fluent languaging practices and by aiming to transcend current boundaries of discourse so as to legitimise these hybrid language uses. Second, Li argues for the generation of translanguaging spaces, that is, spaces that encourage practices which explore the full range of users’ repertoires in creative and transformative ways.

There is an obviously radical agenda at work here: translanguaging foregrounds students’ multilinguistic knowledge and practices as “assets” and insists that these be fully utilized in classroom communication and in the wider community. Classroom praxis must exemplify the disruption of “subtractive” approaches to language education and “deficit” language policies. García & Wei (2014) emphasise the importance of “criticality, critical pedagogy, social justice and the linguistic human rights agenda” (p. 3), and of alignment with a socio-cultural perspective to applied linguistics.

“Standardized English” has become the focus of criticism from a wide range of scholars and researchers, and to those mentioned above, we should add Nelson Flores and Jonathan Rosa (see, for example, Flores & Rosa, 2015; Rosa & Flores, 2017) and Valentina Migliarini and Chelsea Stinson (see Migliarini & Stinson, 2021). Flores and Rosa argue that standardized linguistic practices are demonstrations of raciolinguistic ideologies, and that language education expects language-minoritized students to model their linguistic practices after the white speaking subject, “despite the fact that the white listening subject continues to perceive their language use in racialized ways” (Flores & Rosa, 2015, p. 149). Migliarini & Stinson (2021) use the Disability Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) solidarity framework “to challenge the deficiency lens through which students at the intersections of race, language, and dis/ability are constantly perceived”, arguing that this has “the potential to create more authentic solidarity with multiply marginalized students” (p. 711). DisCrit solidarity attempts to transform teachers’ understanding of power relations in the classroom “so that they are not steeped in color-evasion and silent on interlocking systems of oppression”. The framework also offers the opportunity to interrogate the ways ableism and linguicism reproduce inequities for students with disabilities. The DisCrit framework embraces translanguaging “as a strategic process (García, 2009b), theory of language (Wei, 2018), and as pedagogy (Garcia, 2009a) which conceptualizes the linguistic practices and mental grammar(s) of multilingual people” (Migliarini & Stinson, 2021, p. 713).

I remain mystified by all this stuff, and I’ve never seen or heard any coherent account of what it all means for the practice of ELT, i.e. a description of the radical, transformative changes which should be made to current syllabuses, materials, pedagogic procedures and assessment tools. And, at a more academic level, while I have no reason to think that any of the sources cited above intended the consequence, it’s a fact that most of the post graduate students I know who are drawn to the views and approaches sketched above are fervent in their commitment to sociolinguistics, and express hostility towards the work of psycholinguists working on cognitive theories of SLA, particularly those who claim to be carrying out scientific research. They frequently refer disparagingly to “positivism”, or to the “positivist paradigm” and express their support for “rebels” like Schumann, Lantolf, Firth & Wagner, and Block who, in the 1990s, tried to rock the positivist boat in which, they suggested, most SLA scholars so smugly sailed. I’ve done posts on this “social turn” during the year, deploring the relativist epistemology in particular and critical social justice in general. It’s particularly sad for me to see Professor Li Wei become Director and Dean of the Institute of Education, where I did my MA and PhD with Prof. Henry Widdowson, Guy Cook, Peter Skehan, and Rob Batstone.

References

Block, D. (1996). Not so fast: some thoughts on theory culling, relativism, accepted findings and the heart and soul of SLA. Applied Linguistics 17,1, 63-83.

Ellis, N. (2019) Essentials of a Theory of Language Cognition. Modern Language Journal. Free Downlad here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/modl.12532,

Firth, A., & Wagner, J. (1997). On discourse, communication, and (some) fundamental concepts in SLA research. Modem Language Journal, 81,3, 285-300.

Firth, A., & Wagner, J. (1998). SLA property: No trespassing! Modem Language Journal, 82, 1, 91-94.

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education. Harvard Educational Review, 85, 2, 149–171.

Garcia, O. & Wei, L. (2014) Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism, and Education. NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

Lantolf, J. P. (1996a). SLA Building: Letting all the flowers bloom. Language Learning 46, 4, 713-749.

Lantolf, J. P. (1996b). Second language acquisition theory building? In Blue, G. and Mitchell, R. (eds.), Language and education. Clevedon: BAAL/ Multilingual Matters, 16-27.

Lewis, G., Jones, B., & Baker, C. (2012a) Translanguaging: origins and development from school to street and beyond. Educational Research and Evaluation, 18, 7, 641-654.

Lewis, G., Jones, B., & Baker, C. (2012b) Translanguaging: developing its conceptualisation and contextualization. Educational Research and Evaluation, 18, 7, 655 – 670.

Migliarini, V., & Stinson, C. (2021). Disability Critical Race Theory Solidarity Approach to Transform Pedagogy and Classroom Culture in TESOL. TESOL Journal, 55, 3, 708-718.

Phillipson, R. (2018) Linguistic Imperialism. Downloaded 28 Oct. 2021 from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/31837620_Linguistic_Imperialism_R_Phillipson

Rosa, J., & Flores, N. (2017). Unsettling race and language: Toward a raciolinguistic perspective. Language in Society, 46, 5, 621-647.

Schumann, J. (1983). Art and Science in SLA Research. Language Learning 33, 49-75.

Books

These are the books I most enjoyed in 2023.

We are electric by Sally Adee

This is the best pop science book I’ve read for years. A “must read” that’s not only important but a real pleasure to read. Here’s the blurb:

You may be familiar with the idea of our body’s biome – the bacterial fauna that populates our gut and can so profoundly affect our health. In We Are Electric we cross the next frontier of scientific understanding: discover your body’s electrome.

Every cell in our bodies – bones, skin, nerves, muscle – has a voltage, like a tiny battery. This bioelectricity is why our brains can send signals to our bodies, why we develop the way we do in the womb and how our bodies know to heal themselves from injury. When bioelectricity goes awry, illness, deformity and cancer can result. But if we can control or correct this bioelectricity, the implications for our health are remarkable: an undo switch for cancer that could flip malignant cells back into healthy ones; the ability to regenerate cells, organs, even limbs; to slow ageing and so much more.

In We Are Electric, award-winning science writer Sally Adee explores the history of bioelectricity: from Galvani’s epic eighteenth-century battle with the inventor of the battery, Alessandro Volta, to the medical charlatans claiming to use electricity to cure pretty much anything, to advances in the field helped along by the unusually massive axons of squid. And finally, she journeys into the future of the discipline, through today’s laboratories where we are starting to see real-world medical applications being developed.

The New Puritans by Andrew Doyle

I don’t know of any really good book that cogently rebuts the theology of critical social justice, but “The New Puritans”, while a bit patchy, not always as well-argued as it could be, and relying on debateable core liberal values, does a good job of describing and evaluating the “religion of Social Justice”. “Cynical Theories” by Pluckrose & Lindsay makes a good companion, but it has an even more informal, clearly one-sided and less rigorous style.

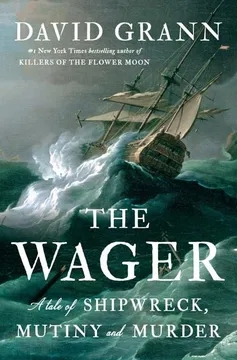

The Wager by David Grann

“A real page turner!” “I couldn’t put it down!” Etc. This is the first David Grann book I’ve read, and now I’ve got the rest lined up. Here’s an Amazon review:

In the first half of the 18th century, Britain already had the most powerful navy in the world. But financing that navy was a huge burden on the Crown and England had not yet achieved the wealth that the industrial revolution and its own colonization efforts would later bring. The answer: intercept the gold and silver that Spanish ships were bringing home from its New World colonies.

Author David Grann is able to tell not only this larger story but also to resurrect one of the most astonishing seafaring events of the time. A ship named “The Wager” was to be part of a British fleet that would intercept gold-laden Spanish vessels in what was officially-sanctioned piracy. As the book’s cover indicates, what then transpired was shipwreck, mutiny and murder. This is also the story of unexpected survival and efforts in an Admiralty court back in England to establish the truth of what happened.

The Wager survived the perilous passage around the treacherous Cape Horn, only to run aground and break up on the rocks of an uninhabited island off Patagonia. There were no animals or other significant source of food on the island. The crew soon divided into two factions, one supporting Captain Cheap who wanted to build a vessel out of timbers salvaged from the shipwreck and continue up the Pacific coast of South America to engage Spanish ships. The other group was led by Buckeley, who wanted to build a vessel to return to England. The situation was so dire it would seem impossible that either group would survive.

Improbably a few men did make their way back to England to be hailed as heroes. That is, until a second group, including Captain Cheap, also arrived. This forms the final chapter of the story of The Wager and the launch of an inquiry to establish the truth.

Faced by death by hanging if they were found guilty of mutiny or of discipline if they failed their duty, each survivor told his story. “Members of the Admiralty found themselves confounded by competing versions of events,” the author tells us. The result was unexpected, but only if one fails to consider that the leaders of an institution, in this case the Royal Navy, have as their first priority the preservation of that institution and the protection of its reputation.

This is a wonderfully-written book; Grann certainly lives up to his reputation as a masterful story teller.

When we cease to understand by Benjamin Labatut

I’ve been meaning to read this for ages and it didn’t disappoint. Phillip Pullman calls it “a monstrous ad brilliant book”, William Boyd says it’s “mesmerising and revelatory”. It’s a dystopian nonfiction novel set in the present. It asks “Has modern science and its engine, mathematics, in its drive towards “the heart of the heart”, already assured our destruction?” It goes at a truly furious pace and before you know it, you’ve finished it. A few minutes sitting with the book on your lap looking out the window onto a nice rural landscape are recommended.

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to you all!

A wonderful blog, Geoff. Very eclectic and some nice narratives included.

Why is it particularly sad to see Li Wei become dean of the IOE? I found his ideas on translanguaging and the inter-relationship between a person’s different languages and their broader identity rather interesting, but don’t know too much more about him. Just asking, as you understand the context much more than me. I also did a pgce and MA at ioe so genuinely interested as to why you’re upset at his appointment.

Thanks for your comments. I find Translanguaging very “weak” – an expression of the critical social justice movement which relies on relativism, obscurantism and posturing. As I said, I can’t see what it contributes to education in general or to ELT in particular. I think of Thomas Pynchon’s line in “V”: “”what was the tag-end of an age if not that sort of imbalance, that tilt toward the more devious, the less forceful?” When I was at IOE, I found it buzzing, vibrant, foreceful, my idea of what a university department should be. I’m sure I’d feel very uncomfortable surrounded by all those fervent sociolinguists championing the causes of ridiculuously-defined, oppressed identity groups.