Introduction

Currently, Marek Kiczkowiak runs TEFL Equity Advocates, the TEFL Equity Academy and Academic English Now, but there are hints of even greater ventures in the pipeline. In a recent video (3 Lessons From Making $70k A Month Teaching English Online), Kiczkowiak boasts of making $70,000 a month from Academic English Now, and announces that he’s ready to share the secrets of his success with teachers everywhere so that they can “start and grow a wildly profitable ELT business that makes you at least $30,000 a month”. (Just by the way, I urge you to watch the “3 lessons” video. It’s a masterclass in slick promotion and the expertese on show contrasts dramatically with the quality of Kiczkowiak’s academic work.) Well, if he himself can make $70,000 a month income, doesn’t that show he’s the man to help EFL teachers make $30,000 a month? Well of course it does. Just phone him for a friendly chat and sign the contract; it’s as simple as that.

Or is it? There are, I think, a few doubts about this rapidly-expanding business endeavour, fuelled by Kiczkowiak’s “one trick pony” academic credentials and his business practices.

History

Kiczkowiak became well-known in ELT circles in 2016 when he gave a presentation at the IATEFL conference calling out employers who used a “Native Speakers Only” policy. He set up a web site called TEFL Equity Advocates to fight the cause of NNESTs, which quickly gained a large following. By the end of the year, promotional material for training courses at his TEFL Equity Academy were being displayed on the front page of his TEFL Equity Advocates web site. I pointed out this conflict of interests on my blog, arguing that Kiczkowiak had developed a powerful brand to promote the cause of fighting discrimination against NNESTs and subsequently used that brand name to promote his own private commercial interests. Kiczkowiak hotly denied the “accusations”, but as Russell Crew-Gee pointed out in the “Comments” section, “the Equity Academy is clearly present as a link on the front page of the TEFL Equity Advocates web page. Hence, Geoff’s premise that the Academy is being promoted directly by the Equity Advocacy website is undeniable, a Factual Reality”.

After making a few changes to his website, Kiczkowiak continued to use the TEFL Equity Advocates brand to promote his own commercial, teacher training courses. I reckon that the goodwill created by the TEFL Equity Advocacy activities definitely benefited Kiczkowiak’s private commercial interests, and his inability to accept this fact makes me question his business ethics.

Metamorphosis

From 2016 on, Kiczkowiak continued to champion both his cause and his courses, but he also did a PhD and published articles in an assortment of journals. Soon, a new persona emerged: Marek Kiczkowiak, the Widely-Puublished-Whiz-Kid-Academic, ready and able to help aspiring academics write dazzling PhD theses and academic articles in not much more time than it takes to transfer a few thousand dollars from your account to his.

Apart from his PhD (two a penny these days, eh?), what are Kiczkowiak’s credentials? I looked on Google Scholar and found these (the 2 columns on the right give citations and year of publication):

I’ve rarely seen a list that more strongly indicates a “one trick pony”, a term used in academia to describe a member of staff with an unacceptably narrow range. These days, nobody expects any Leornado de Vinci-like polymaths to fight for one of the diminishing number of tenured postions available in university departments, but nevertheless, there are quite high standards to meet, and Kiczkowiak’s publications just don’t meet them. The one topic he writes about is not just extremely limited, it’s contentious. ”Native speakerism” is the overtly political, obscurantist construct of A. Holliday, a blustering scholar who talks nonsense with all the conviction of a relgious zealot.

A further doubt about Dr. Kiczkowiak arises from an inspection of where his articles were published. IATEFL Voices, University of York, Teacher Education and Development Journal, British Council Voices Magazine, TESL-EJ, and a short entry to an encyclopedia are hardly the journals where all the best academics seek to get published.

Then there’s the content. Native-speakerism and the complexity of personal experience: A duoethnographic study by RJ Lowe and M Kiczkowiak, consists of conversations between the two authors about being native or non-native speaker teachers of English – Lowe’s the NEST and Kiczkowiak is the NNEST. Data from the duoethnographic study (or “chats” as they’re called in plain English) indicate “that the effects of native-speakerism can vary greatly from person to person based on not only their “native” or “non-native” positioning, but also on geography, teaching context and personal disposition”. Who knew!

The article begins:

“Native-speakerism is a term coined and described by Holliday (2003, 2005, 2006), which is used to refer to a widespread ideology in the English Language Teaching (ELT) profession whereby those perceived as “native speakers” of English are considered to be better language models and to embody a superior Western teaching methodology than those perceived as “non-native speakers”. This ideology makes extensive use of an “us” and “them” dichotomy where “non-native speaker” teachers and students are seen as culturally inferior and in need of training in the “correct” Western methods of learning and teaching. Native-speakerism also makes extensive use of what Holliday (2005) calls “cultural disbelief” (see also Holliday, 2013, 2015); a fundamental doubt that “non-native speakers” can make any meaningful contributions to ELT.

Holliday’s initial description of native-speakerism as an ideology that benefits “native speakers” to the detriment of “non-native speakers” has been recently criticised by Houghton and Rivers, who, in their edited volume (Houghton & Rivers (2013) show that “native speakers” can also be affected negatively by the ideology. Consequently, native-speakerism can now be understood as an ideology which, while privileging the knowledge and voices of Western ELT institutions, uses biases and stereotypes to classify people (typically language teachers) as superior or inferior based on their perceived belonging or lack of belonging to the “native speaker” group (Holliday, 2015); Houghton & Rivers, 2013)”.

Now let’s see how the article Confronting Native Speakerism …, written a year later, begins:

“‘Native speakerism’ is a term coined by Holliday (2005, 2006) by which he referred to the belief that the ideals of English Language Teaching (ELT) methodology and practice originate in Western culture, which in turn is embodied by a ‘native speaker’ of English, who is deemed the ideal teacher. Houghton and Rivers (2013, p. 14) reconceptualise this definition to show that both ‘native’ and ‘non-native speakers’ can be negatively impacted by native-speakerism, which is now understood as: a prejudice, stereotyping and/or discrimination, typically by or against foreign language teachers, on the basis of either being or not being perceived and categorized as a native speaker of a particular language. (…) Its endorsement positions individuals from certain language groups as being innately superior to individuals of other language groups”. Do you spot any similarities?

Next, the “article” Teaching English as a lingua franca: The journey from EFL to ELF . Oh, it’s not actually an article published in an academic journal, it’s an extract from a book.

Seven principles for writing materials for English as a lingua franca is a short piece for the ELTJ which gives advice to materials writers such as “use authentic E(LF)nglish rather than ‘native speaker’ corpora” and “use Multilingual E(LF) rather than monolingual ‘native speaker’ language”. The claim is that these “principles” should help to cancel the contribution current coursebooks make to “the entrenchment of what Holliday (2005) has referred to as the ideology of native speakerism”.

Using awareness raising activities on initial teacher training courses to tackle ‘native-speakerism’ begins “Native Speakerism is a term coined by Holliday (2005, 2006) which refers to the belief that the Native English Speaker (NES) is the embodiment of the values and ideals of English Language Teaching (ELT) pedagogy and knowledge”.

Recruiters’ Attitudes to Hiring ‘Native’ and ‘Non-Native Speaker’ Teachers: An International Survey is the only article that has merit, in my opinion. The survey is competently designed and implemented and its findings are clearly and honestly set out.

You’ll have to take my word for it when I say that the rest of the articles are further variations on the same theme, and allow me to deal with just one more: the 2021 article by Kiczkowiak and Lowe, “Native-speakerism in English language teaching: ‘Native speakers’ more likely to be invited as conference plenary speakers”. This is one of the very few Kiczkowiak texts that actually discusses what the terms “native speaker” and “non-native speaker” refer to. The authors begin by explaining why they diasagree with the concepts of ‘native speaker’ and ‘non-native speaker’. These terms have been used in SLA research as “neutral scientific labels” primarily based on early exposure to the language, but Kiczkowiak and Lowe prefer to see them as “social and political constructs”, which “arose in the context of city states attempting to consolidate their power and develop ideas of shared identity among the citizenry (Hackert 2012; Train 2009)”.

The authors then settle into their favorite territory: Holliday land. Any use of the terms NS and NNS labels is “ideological, chauvinistic and divisive” and the continuous use of the labels “routinises and normalises them (Holliday 2013, 2018)”. The authors go on to explain that, despite their enthusiastic endorsement of Holliday’s views, they feel forced to use the terms native speaker and non-native speaker in their analysis, but to partially cover their embarrassment, they follow Holliday (2005) by placing the terms in inverted commas to remind themselves and their readers “of their ideological and subjective nature”. Having apologised for the brevity of their review, the authors move to a report of their study, which found that “out of a total of 416 plenaries, only 25 per cent were given by ‘non-native speakers’ and 0.06 per cent by speakers of colour”.

The discussion of “native speakerism” in the article is entirely inadequate and the poor standard of academic discussion evdent here extends to, indeed pervades, all of Kiczkowiak’s articles. In this article, as in so many others, the authors simply assert this that and the other about the terms native speaker and non-native speaker and the construct of native speakerism without going to the trouble of describing or engaging in any critical evaluation of other views. Below is a quick sketch of one such view.

Native speakerness is a psychological reality.

In the domain of SLA research, native speakers of language X are people for whom language X is the language they learnt through primary socialization in early childhood, as a first language. To paraphrase Long (2007, 2015), the psychological reality of native speakerness is easily demonstrated by the fact that we know one, and who isn’t one, when we meet them, often on the basis of just a few utterances. When English native speakers are presented with recorded stretches of speech by a large pool of NSs and NNSs and asked to say which are which, they distinguish between them with reliability typically well above .9. How do they do this, and why is there so much agreement if, according to Holliday, there’s no such thing as a NS?

For the last 70 years, the term “native speaker” has been used in SLA studies to investigate the failure of the vast majority of post adolescent L2 learners to achieve what Birdsong refers to as “native like attainment”. “On the prevailing view of ultimate attainment in second language acquisition, with few exceptions, native competence cannot be achieved by post pubertal learners “(Birdsong 1992).

The specific claim that very few post adolescent L2 learners attain native like proficiency is supported by a great deal of empirical evidence (see, e.g., reviews by Long 2007, Harley and Wang 1995; Hyltenstam and Abrahamsson 2003). When trying to explain why most L2 learners don’t attain native competence, scholars have investigated various “sensitive periods”. Long (2007) argues that the issue of age differences is fundamental for SLA theory construction. If the evidence from sensitive periods shows that adults are inferior learners because they are qualitatively different from children, then this could provide an explanation for the failure of the vast majority of post adolescent L2 learners to achieve Birdsong’s “native like attainment”. On the other hand, if we want to propose the same theory for child and adult language acquisition, then we’ll have to account for the differences in outcome some other way; for example, by claiming that the same knowledge and abilities produce inferior results due to different initial states in L1 acquisition and L2 acquisition. Either way, the importance of the existence (or not) of sensitive periods for those scholars trying to explain the psychological process of SLA suggests the usefulness of using the native speaker as a measure of the proficiency of adult L2 learners.

Most importantly, using the NS and NNS terms does not, pace Kiczkowiak, entail assuming that native speakers of English are better language models or better teachers than non-native speakers.

Assertions don’t make an argument

Kiczkowiak cites the work of scholars who argue against the view outlined above, including some, like Vivian Cook, who do it very persuasively. The trouble is that Kiczkowiak doesn’t bother to lay out the argument made by these scholars; he simply states their assertions as if their persuasiveness spoke for itself. In the Kiczkowiak and Lowe (2021) article, work by Dewaele, Bak, and Ortega (2021); Hackert (2012); Train (2009); Aboshiha (2015); Amin (1997); Kubota and Fujimoto (2013) Ruecker and Ives (2015); Rampton (1990); Paikeday (1985); Cook (2001); Jenkins (2015); Dewaele (2018); and others are cited, but no attempt is made to present or critically discuss their views. Thus Kiczkowiak makes the elementary mistake made by inexperienced postgrad students: he cites scholars’ assertions as if doing so automatically lends support to his own argument. In any case, the paper, like all the others, is hampered by having to start from Holliday’s assumption that the key terms under discussion don’t actually exist.

Holliday’s “racist native speakerism” and “essentialism”

The most frequently cited source in all Kiczkowiak’s articles about native speakerism is, of course Holliday. As we’ve seen, Kiczkowiak begins quite a few of his articles by giving a summary of Holliday’s construct of native speakerism, a construct which Kiczkowiak never attempts to evaluate, presumeably because he’s so thoroughly convinced of its truth, including Holliday’s assertion that using the acronyms NS and NNS is clear evidence of racism.

In a post on his blog, Holliday says that “In academia the established use of ‘native speaker’ as a sociolinguistic category comes from particular paradigmatic discourses of science and is not fixed beyond critical scrutiny”. This is the kind of bunkum that so often goes unchalleged these days and bad scholars like Kiczkowiak actually emulate such incoherent claims. What does the phrase “particular paradigmatic discourses of science” refer to? Scientific method, that’s what. Holliday asserts that adopting a realist epistemology, and carrying out quantitative research by testing well-articulated hypotheses with empirical evidence and logical argument is part of a “mistaken paradigm”. When one compares the results of adopting this paradigm (visit the Science Museum in South Kensington or browse their website) with the results of adopting Holliday’s approach to research (I don’t know of any important results), one quickly appreciates the proposterousness of that claim. Anyway, since in the field of SLA research there isn’t – and never has been – any general theory of SLA with paradigm status, talk of paradigms (like talk of “imagined objective ‘science’” and labels placed in inverted commas that refer to things that “do not actually exist at all”) belongs only to the topsy-turvy world of post-modern sociology.

Holliday asserts that when we refer to people as ‘non-native speakers’, we imply that they are “culturally deficient”, and that this amounts to “deep and unrecognised racism”. Referring to people as non-native speakers “defines, confines and reduces” them by referring to their culture in a way that evokes “images of deficiency or superiority – divisive associations with competence, knowledge and race – who can, who can’t, and what sort of people they are”. These sweeping assertions are “supported” by Holliday’s construct of essentialism. At a minor conference held somewhere in England in 2019, Holliday explained:

Essentialism is to do with ‘Us-Them’ discourse. ‘They’ are essentially different to ‘Us’ because of their culture…… There’s no way we can be the same. There’s something absolutely separate about us and them. ……. Culture then becomes a euphemism for race. It’s essentially racist to imagine a group here and a group there who are essentially different to each other. That is the root of racism…….. Any group who is put over there and defined as being different to you, that is the basis of racism. …………… Grand narratives define “us” and “them” by fixity and division. We are different to those people, we have to be in order to survive. .. You brand your nation as being different to those people, in a superior or inferior way.

As evidence for his thesis, Holliday gives the example of a Chinese student who told him he’d turned down a fantastic job in Mexico “because Mexico is not as good as Britain”. Holliday explains: He had a hierarchy in his head. I challenge everybody in this room …. We all position ourselves …There’s no such thing as talking about culture in a neutral way; we just cannot. Everybody is positioning themselves in a hierarchy.

In another meaning-drenched anecdote, Holliday recalls the time he was in Istanbul interviewing colleagues. “We were sitting right on the Bosphorus. And everything that was East was inferior, and everything that was West was superior. This came out, very very clear; very very clear. Even inside Turkey”. The obvious question to ask is: How does Holliday know all this stuff about what people are thinking? How did he know that his Chinese student had a hierarchy in his head, or that his companions in Istanbul made the “essentialist statement” that “‘They’ are essentially different to ‘Us’”? Why should we believe for a second that Holliday has somehow correctly read people’s minds?

Lets suppose we ask a group of scientists, born and raised in France, who all adopt a realist epistemology and carry out quantitative research, to watch a documentary about life in Beijing where the locals are shown working and playing and doing the everyday things they do. Regardless of what they might say, Holliday will insist that the scientists’ “positivist ideology” will make them all think, consciously or not: “Those people are essentially different to us. There’s no way we can be the same. There’s something absolutely separate about us and them”. Holliday will also insist that they’re all racists. If the scientists deny these charges, Holliday will take the approved line of the critical social justice brigade and say they’re blind to their racism. They can’t help themselves: they can’t escape their cultural influences and the consequences of their “positivist ideology”.

In short, “postivists” are bad people. The good people are epistemological relativists like Holliday, those who rely on the interpretation of subjective experiences and who reject the scientific, “positivist paradigm”. To be clear: Holliday’s commitment to a qualitative, ethnographic methodology and to a constructivist, relativist epistemology amounts to abandoning reason. Having done so, Holliday is free to harangue people in his zealous pursuit of racists and all the other bad people whose ideologies he finds so offensive. Holliday limits the scope of his descriptions to a single, preferred interpretation which is not just partial, but also ideologically blinkered. It’s scary.

Kiczkowiak The Scholar

Kiczkowiak leans on Holliday. Holliday’s views provide the theoretical underpinning for Kiczkowiak’s rants against “native speakerism”. Search Kiczkowiak’s narrow little oevre and you’ll find no trace of originality, or valuable insights, or critical acumen, or any appreciation for what academic work is really about. When attempting to deal with other scholar’s work, Kiczkowiak conflates the work of scholars who have little in common, failing to acknowledge the very different views of V. Cook , Holliday and Widdowson, for example, or the important differences between the group that comprises critical applied linguists, including Phillipson, Pennycock, Canagarajah, and Edge. More generally he fails to differentiate between those academics who oppose discrimination against NNESTs (just about everybody) and those who belong to the critical social justice movement, whose views Kiczkowiak manages to simultaneously applaud and misrepresent. In short, Kiczkowiak’s oeuvre gives scant cause for trusting his judgements or advice on writing academic texts.

Current Situation

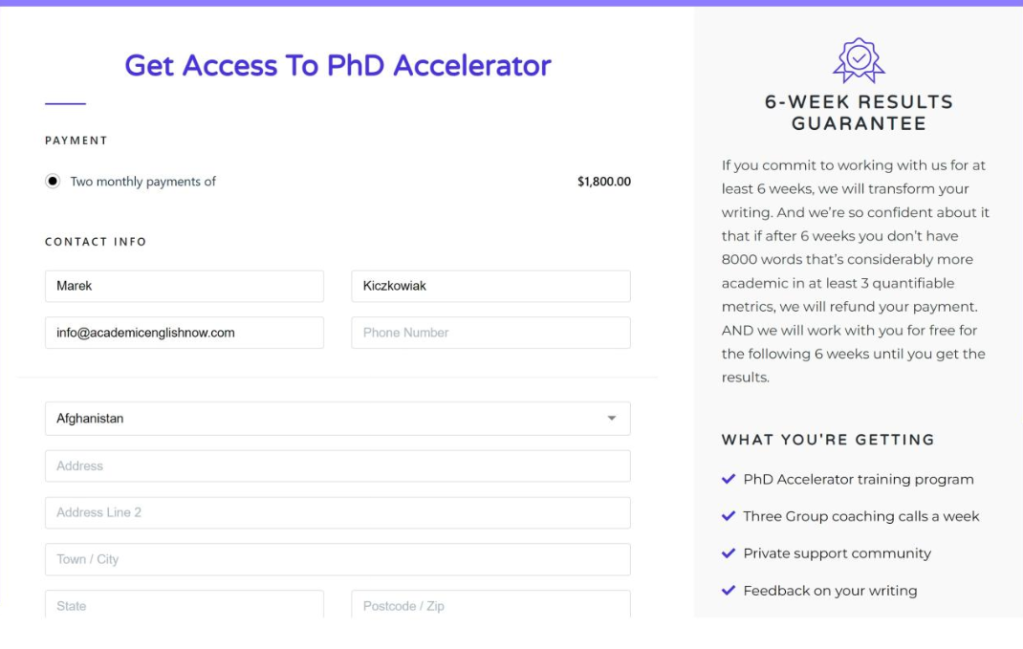

Kiczkowiak has morphed from teacher, NNEST crusader and teacher trainer in 2016 to CEO of Academic English Now in 2023. Currently, he’s charging “hundreds of students” $1,800 a month for his services and he’s very keen to“grow the business” as they say. My advice to all his potential clients is to look carefully at his credentials, his record and his products before handing over a cent. Read the form below carefully and get detailed information about “What you’re getting” (bottom right).

- What exactly does the “training program” consist of?

- What are “Group coaching calls”?

- How many attend?

- How long are they?

- What’s the “Private support community”?

- What does the feedback consist of?

- What happens if I’m not satisfied?

An Unsatisfied Customer

I wrote to the person concerned, but I haven’t had a reply, so I won’t name her. I saw her correspondence with Kiczkowiak by going to his profile and looking at “Comments”.

Ms J., as I’ll call her, questions “the integrity of the program” and Kiczkowiak’s “true intentions”. She suggests that the program and the refund policy may prioritize financial gain over the well-being and satisfaction of clients.

In an open letter to Researchers and PhD candidates, Ms. J. shares her personal experience and provides a warning to those considering the PhD Accelerator Program offered by Kiczkowiak and his team. Ms. J says she joined the program out of desperation, without the chance to see any independent reviews which might have “revealed the truth about its actual value and efficacy”. She found the program’s claims of personalized action plans, tailored mentorship, and comprehensive support to be “misleading”, and she felt that the program failed to deliver on its promises, instead preying on the vulnerability and desperation of PhD students. She considers the cost of $2,400 to be “exorbitant” far outweighing the actual value provided, and warns about the difficulties of getting a refund: “the refund policy is designed to protect the program’s financial interests rather than prioritize client satisfaction”.

I understand that there was an exchange of comments between Miss J. and staff of Kiczkowiak’s “Academy”, including this from the boss himself:

Dear ……,

our refund policies are clearly stated on the website: https://academicenglishnow.com/terms-and-conditions The link to the terms is also available on the checkout page, and before purchasing, you have to click that you have read and agreed to the terms. The refund policy is also clearly stated on the right hand side (see the screenshot). Plus, you’re not really coerced to do anything. You can decide whether you want to enrol or not yourself. As I mentioned in my previous emails, we do not issue refunds that do not fit our refund policy, which is clearly disclosed. You also mentioned several times that the mentorship offered on the program was not up to standard. However, it’s important to point out here that you didn’t engage with your coach despite follow-ups from her.

Conclusion

Marek Kiczkowiak brags about selling “hundreds” of PhD candidates products that cost $1,800 a month. Not content with his current $70,000 a month income, he wants to attract a wider customer base, inviting EFL teachers everywhere to pay him a modest few thousand dollars so that he can lead them out of penury towards an annual income of $360,000! Wow! Can you believe it? I, for one, most certainly cannot.