The Shift From a Behaviourist to a Cognitivist View of SLA

Before proceeding with the review of SLA, I need to recap the story so far, in order to highlight the difference between two contradictory epistemologies. I do so for two reasons. Firstly, we are seeing a return to behaviourism in the guise of increasingly popular, and increasingly misinterpreted, usage-based theories of language learning such as emergentism. The epistemological underpinnings of these theories are rarely mentioned, particularly by ELT teacher trainers who either clumsily endorse them or airily dismiss them. Secondly, it gives me an opportunity to restate the implications of the shift to a more cognitive view of the SLA process.

Behaviourism

Behaviourism has much in common with logical positivism, the most spectacularly misguided movement in the history of philosophy. Chasing the chimera of absolute truth, the logical positivists, most famously, those in the Vienna Circle formed in the early 1920s, had as their goal nothing less than to clean up language and put science on a sure empirical footing. The mad venture they embarked on didn’t last long – it was all over before the second world war broke out, leaving a legacy of unusually unpleasant academic in-fighting behind it.

But behaviourism has a much longer history. It began with the 1913 work of pioneering American psychologist John B. Watson, and went on when B.F. Skinner took over after WW2. Watson was influenced by the work of Pavlov (1897) and Bekhterev (1896) on conditioning of animals, but later was much taken by the works of two stars of the logical positivist movement, namely Mach (1924) and Carnap (1927) from the Vienna School, under whose influence he attempted to make psychological research “scientific”, by using only “objective procedures”, such as laboratory experiments which were designed to establish statistically significant results. Watson formulated a stimulus-response theory of psychology according to which all complex forms of behaviour are explained in terms of simple muscular and glandular elements that can be observed and measured. No mental “reasoning”, no speculation about the workings of any “mind”, were allowed. Thousands of researchers adopted this methodology, and from the end of the first world war until the 1950s an enormous amount of research on learning in animals and in humans was conducted under this strict empiricist regime.

In 1950 behaviourism could justly claim to have achieved paradigm status, and at that moment, B.F. Skinner became its new champion. Skinner’s contribution to behaviourism was to challenge the stimulus-response idea at the heart of Watson’s work and replace it by a type of psychological conditioning known as reinforcement (see Skinner, 1957, and Toates and Slack, 1990). Important as this modification was, it is Skinner’s insistence on a strict empiricist epistemology, and his claim that language is learned in just the same way as any other complex skill is learned, by social interaction, that is important here.

The strictly empiricist epistemology of behaviourism outlaws any talk of mental structure or of internal mental states. While it’s perfectly OK to talk about these things in every day parlance, they have no place in scientific discourse. Strictly speaking – which is how scientists, including psychologists should speak – there is no such thing as the mind, and there is no sense (sic) in talking about feelings or any other stuff that can’t be observed by appeal to the senses. Behaviourism sees psychology as the science of behaviour, not the science of mind. Behaviour can be described and explained without any ultimate reference to mental events or to any internal psychological processes. The sources of behaviour are external (in the environment), not internal (in the mind). If mental terms or concepts are used to describe behaviour, then they must be replaced by behavioural terms or paraphrased into behavioural concepts.

Behaviour is all there is: humans and animals are organisms that can be observed doing things, and the things they do are explained in terms of responses to their environment, which also explains all types of learning. Learning a language is like learning anything else – it’s the result of repeated responses to stimuli. There are no innate rules by which organisms learn, which is to say that organisms learn without being innately or pre-experientially provided with explicit procedures by which to learn. Before organisms interact with the environment they know nothing – by definition. Learning doesn’t consist of rule-governed behaviour; learning is what organisms do in response to stimuli. An organism learns from what it does, from its successes and mistakes, as it were.

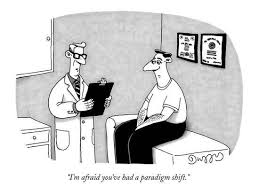

The minimalist elegance of such a stark view is impressive, even attractive, – especially if you’re sick of trying to make sense of Freud, Jung, or Adler, perhaps – but it makes explaining unobservable phenomena, whatever they happen to be, problematic, to say the least. Still, for Amerrican scholars immersed in the field of foreign language learning in the post WW2 era, a field not exactly renowned for its contributions to philosophy or scientific method, behaviourism had a lot going for it: an easily-grasped theory with crystal clear pedagogic implications. The opposition to the Chomskian threat was entirely understandable, but, historically at least, we may note that their case collapsed like a house of cards. Casti (1989) points out that a Kuhnian paradigm shift is nowhere more completely and swiftly brought about in the 20th century than by Chomsky in linguistics.

In his 1957 Verbal Behaviour, Skinner put forward his view that language learning is a process of habit formation involving associations between an environmental stimulus and a particular automatic response, produced through repetition with the help of reinforcement. This view of learning was challenged by Chomsky’s (1959) Review of Skinner’s Verbal Behaviour, where he argued that language learning was quite different from other types of learning and could not be explained in terms of habit-formation. Chomsky’s revolutionary argument, begun in Syntactic Structures (1957), and consequently developed in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965) and Knowledge of Language (1986) was that all human beings are born with an innate grammar – a fixed set of mental rules that enables children to create and utter sentences they have never heard before. Chomsky asserted that language learning was a uniquely human capacity, a result of Homo Sapiens’s possession of what Chomsky at first referred to as a Language Acquisition Device. Chomsky developed his theory and later claimed that language consists of a set of abstract principles that characterise the core grammars of all natural languages, and that the task of learning one’s L1 is thus simplified since one has an innate mechanism that constrains possible grammar formation. Children do not have to learn those features of the particular language to which they are exposed that are universal, because they know them already. The job of the linguistic was to describe this generative, or universal, grammar, as rigorously as possible.

So the lines are clearly drawn. For Skinner, language learning is a behavioural phenomenon, for Chomsky, it’s a mental phenomenon. For Skinner, verbal behaviour is the source of learning; for Chomsky it’s the manifestation of what had been learned. For Skinner, talk of innate knowledge is little short of gibberish; for Chomsky it’s the best explanation he can come up with for the knowledge children have of language.

In SLA Part 1, I described how, under the sway of a behaviourist paradigm, researchers in SLA viewed the learner’s L1 as a source of interference, resulting in errors. In SLA Part 2, I described how, under the new influence of a mentalist paradigm, researchers now viewed learners as drawing on their innate language learning capacity to construct their own distinct linguistic system, or interlanguage. The view of learning an L2 changes from one of accumulating new habits while trying to avoid mistakes (which only entrench bad past habits), to one of a cognitive process, where errors are evidence of the learner’s ‘creative construction’ of the L2. Research into learner errors and into learning specific grammatical features, gave clear evidence to support the mentalist view. The research showed that all learners, irrespective of their L1, seemed to make the same errors, which in turn supported the view that learners were testing hypotheses about the target language on the basis of their limited experience, and making appropriate adjustments to their developing interlanguage system. Far from being evidence of non-learning, errors were thus clear signs of interlanguage development.

Furthermore, and very importantly in terms of its pedagogic implications, interlanguage development, seen as a kind of built-in syllabus, could be observed following the same route, regardless of differences in the L1 or of the linguistic environment. It was becoming clear that (leaving aside the question of maturational constraints for a moment) learning an L2 involved moving along a universal route which was unaffected by the L1, or by the learning environment – classroom, workplace, home, wherever. Just as importantly, the research showed that L2 learning is not a matter of successively accumulating parts of the language one bit after the other. Rather, SLA is a dynamic process involving the gradual development of a complex system. Learners can sometimes take several months to fully acquire a particular feature, and the learning process is anything but linear: it involves slowly and unsystematically moving through a series of transitional stages, including zigzags, u-shaped patterns, stalls, and plateaus, as learners’ interlanguages are constantly adjusted, reformulated, and rebuilt in such a way that they gradually approximate more to the L1 model.

A picture is thus emerging of SLA as a learning process with two important characteristics.

- Knowledge of the L2 develops along a route which is impervious to instruction, and

- it develops in a dynamic, nonlinear way, where lots of different parts of the developing system are being worked on at the same time.

As we continue the review, we’ll look at declarative and procedural knowledge, explicit and implicit knowledge, and explicit and implicit learning, and this will indicate the third important characteristic of the SLA process:

3. Implicit learning is the default mechanism for learning an L2.

We’ll then be in a stronger position to argue that teacher trainers who advise their trainees to devote the majority of classroom time to the explicit teaching of a sequence of formal elements of the L2 are grooming those trainees for failure.

For References See “Bibliography ..” in Header