Introduction

In her article “How to use coursebooks and deal with emergent language”, Rachael Roberts says this:

Thornbury’s biggest gripe about coursebooks is the way they are generally built around a structural syllabus. Each unit has a handful of language points (which is what he famously refers to as ‘grammar McNuggets’) and the assumption is that these points will be presented, practised and learnt. It’s admittedly something of a false assumption: language doesn’t develop in a linear and predictable fashion and while we may hope to teach a particular point, ultimately all we can do is to expose students to stretches of language, create opportunities for meaningful dialogue and opportunities to notice and, crucially, enable students to engage with language. But none of this militates against using a coursebook as a basis. (My emphasis)

What, none of it??

Why not? Well first, because

the teacher is there to mediate the material to ensure that the students are engaged and challenged.

For example, in a reading text, ask students to set their own questions before they start reading, based on the title or illustrations. Or get them to use the book’s questions about the text to predict the content of the text.

And second, because teachers can supplement coursebook material

with further noticing, repetition and recycling activities.

For example, teachers can follow up work on language in texts with dictogloss activities, or they can ask students to translate the text into their L1 and later translate it back. Or they can follow up a listening comprehension activity by getting students to listen again; note down language used to give opinions; ask students to remember how the phrases were completed; complete them in different ways; discuss the level of formality and so on; then get students to use them in a discussion. Or ask students to record themselves carrying out a short speaking task and then make a transcription of what they said. The teacher can then reformulate what each student has written and the student can compare their version with the teacher’s version.

That’s it; that’s why coursebooks are OK. Fair enough, you may think; Roberts gives some useful examples of how teachers can mediate and supplement coursebook material.

The article concludes:

A coursebook is like a set of recipes: some people will prefer to stick to the recipe at least to start with and just produce what’s in the book; some will start experimenting and producing their own take on the recipe; and some people just love making everything from scratch. No one wants to live on a diet of ‘grammar McNuggets’, but pre-prepared food (or lessons) can also be nutritious, delicious and definitely labour-saving!

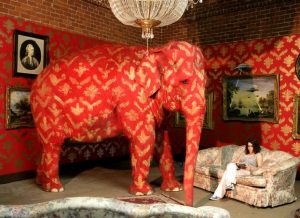

That elephant again

When you get to the end of the article, you realise that Thornbury’s gripe remains unanswered. Coursebooks are used – precisely as Roberts herself says – as the basis for courses of General English; they’re used, that is, to implement a grammar-based, synthetic syllabus by presenting and practicing bits of language in a linear sequence. To assume that these bits of language will be learned in the order and manner in which they’re presented is not just “something of a false assumption”, it’s the fatally-flawed basis of the whole approach, and it doesn’t work. While “we may hope” that when we teach a particular point, the students will learn it, we know enough about interlanguage development to know that our “hope” is completely unreasonable, so we’d be well advised to stop teaching “points” in this way, and to spend the time organising activities that really do create opportunities for meaningful dialogue, and that really do enable students to engage with language.

Roberts, like so many other apologists for coursebook-driven ELT, refuses to acknowledge the elephant in the room: she follows the usual line, referring to coursebooks as mere collections of materials and ignoring the crucial fact that a coursebook (the clue’s in the name) is designed to supply the organising principle, the syllabus, which drives the whole course. It’s NOT just a set of materials which teachers can cherry pick from, it’s a general plan; a route through a General English course. And that route clashes head on with the students’ own internal route of interlanguage development. Robust findings from SLA research tell us that it’s quite literally impossible for students to follow the coursebook’s route.

Junk Food

Roberts’ final remarks about a coursebook being like a set of recipes endorse the “pick and choose” misrepresentation (it’s not a recipe book, IT’S A SYLLABUS!), while inviting us all to enjoy the nutricious, delicious contents. This view is challenged by most experts who have reviewed coursebooks. Not just Thornbury and Meddings, but Mike Long, Stephen Krashen, Peter Robinson, Peter Skehan and a host of other scholars lament the carefully packaged junk food served up. Recall Tomlinson and Masuhara’s conclusion about English File, Outlooks and other such series: they’re bland, unappealing, unchallenging, unimiginative, unstimulating, mechanical, superficial and dull. None of them is likely to to be effective in facilitating long-term acquisition.

Conclusion

The focus of coursebooks is on the explicit learning of language. They lead students along a path that students can’t follow, and they provide too few opportunities for engagement in relevant, challenging communicative activities. That’s what’s wrong with them, and what’s ironic about Robert’s article is that she suggests ways in which teachers can supplement coursebooks by providing even more opportunities for explicit learning. Every one of Robert’s suggestions involves working ON the language rather than working IN the language for some communicative purpose. Like so many other teacher trainers, Roberts treats language as an object to be taught explicitly rather than as a means of communication to be taught mostly implicitly through communicative use.

Reference

Roberts, R. (2015) How to use coursebooks and deal with emergent language. English Australia Journal, 29, 1.

Tomlinson, B. and Masuhara, H. (2013) Adult Coursebooks. ELT Jornal.