Introduction

Jackendoff’s Representational Modularity Theory (Jackendoff, 1992) is a key component in Susanne Carroll’s Autonomous Induction Theory, as described in her book Input and Evidence (2001). Carroll’s book is too often neglected in the SLA literature, and I think that’s partly because it’s very demanding. Carroll goes into so much depth about how we learn; she covers so much ground in so much methodical detail; she’s so careful, so thorough, so aware of the complexities, that if you start reading her book without some previous understanding of linguistics, the philosophy of mind, and the history of SLA theories, you’ll find it very tough going. Even with some such understanding of these matters, I myself find the book extremely challenging. Furthermore, the text is dense and often, in my opinion, over elaborate; you have to be prepared to read the text slowly, and at the same time keep on reading while not at all sure where the argument’s going, in order to “get” what she’s saying.

One criterion for judging theories of SLA is an appeal to Occam’s Razor: ceteris paribus (all other things being equal), the theory with the simplest formula, and the fewest number of basic types of entity postulated, is to be preferred for reasons of economy. Carroll’s theory scores badly here: it’s complicated! Her use of Jackendoff’s theory, and of the Induction Theory of Holland et.al. means that her theory of SLA counts on a variety of formula and entities, and thus it’s not “economical”. On the other hand, it’s one of the most complete theories of SLA on offer.

Over the years, I’ve spent weeks reading Carroll’s Input and Evidence, and now, while reading it yet again in “lockdown”, I’m only just starting to feel comfortable turning from one page to the next. But it’s worth it: it’s a classic; one of the best books on SLA ever, IMHO, and I hope to persuade you of its worth in what follows. I’m going to present The Autonomous Induction Theory (AIT) in an exploratory way, bit by bit, and I hope we’ll end up, eventually, with some clear account of AIT and what it has to say about second language learning, and its implications for teaching.

UG versus UB

In the current debate between Chomsky’s UG theory and more recent Usage-based (UB) theories of language and language learning, most of those engaged in the debate see the two theories as mutually contradictory: one is right and the other is wrong. One says language is an abstract system of form-meaning mappings governed by a grammar (in Chomsky’s case a deep grammar common to all natural languages as described in the Principles and Parameters version of UG), and this knowledge is learned with the help of innate properties of the mind. The other says language should be described in terms of its communicative function; as Saussure put it “linguistic signs arise from the dynamic interactions of thought and sound – from patterns of usage”. The signs are form-meaning mappings; we amass a huge collection of them through usage; and we process them by using relatively simple, probabilistic algorithms based on frequency.

O’Grady (2005) has this to say:

The dispute over the nature of the acquisition device is really part of a much deeper disagreement over the nature of language itself. On the one hand, there are linguists who see language as a highly complex formal system that is best described by abstract rules that have no counterparts in other areas of cognition. (The requirement that sentences have a binary branching syntactic structure is one example of such a “rule.”) Not surprisingly, there is a strong tendency for these researchers to favor the view that the acquisition device is designed specifically for language. On the other hand, there are many linguists who think that language has to be understood in terms of its communicative function. According to these researchers, strategies that facilitate communication – not abstract formal rules – determine how language works. Because communication involves many different types of considerations (new versus old information, point of view, the status of speaker and addressee, the situation), this perspective tends to be associated with a bias toward a multipurpose acquisition device.

Susanne Carroll tries to take both views into account.

Property Theories and Transition Theories of SLA

Carroll agrees with Gregg (1993) that any theory of SLA has to consist of two parts:

1) a property thory which describes WHAT is learned,

2) a transition theory which explains HOW that knowledge is learned.

As regards the property theory, it’s a theory of knowledge of language, describing the mental representations that make up a learner’s grammar – which consists of various classifications of all the components of language and how they work together. What is it that is represented in the learner’s knowledge of the L2? Chomsky’s UG theory is an example; Construction grammar is another; The Competition Model of Bates & MacWhinney (1989, cited in Carroll, 2001) is another; while general knowledge representations, and forms of rules of discourse, Gricean maxims , etc. are, I suppose also candidates.

Transition theories of SLA explain how these knowledge states change over time. The changes in the learner’s knowledge, generally seen as progress towards a more complete knowledge of the target language, need to be explained by appeal to a causal mechanism by which one knowledge state develops into another.

Many of the most influential cognitive processing theories of SLA (Chaudron, 1985; Krashen, 1982; Sharwood Smith, 1986, Gass, 1997, Towell & Hawkins, 1994, cited in Carroll, 2001) concentrate on a transition theory. They explain the process of L2 learning in terms of the development of interlanguages , while largely ignoring the property theory, which they sometimes, and usually vagely, assume is dealt with by UG. New UB theories (e.g. Ellis, 2019; Tomesello, 2003) reject Chomsky’s UG property theory and rely on what Chomsky regards as performance data for a description of the language in terms of a Construction Grammar. More importantly, perhaps, their ‘transition theory’ makes a minimal appeal to the workings of the mind; they’re at pains to use quite simple general learning mechanisms to explain how “associative” learning, acting on input from the environment, explains language learning.

Mentalist Theories

Carroll bases her approach on the view that humans have a unique, innate capacity for language, and that language learning goes on in a modular mind. Here, I’ll leave discussions about the philosophy of mind to one side, but suffice it to say for now that ‘mind’ is a theoretical construct referring to a human being’s world of thought, feeling, attitude, belief and imagination. When we talk about the mind, we’re not talking about a physical part of the body (the brain), and when we talk about a modular mind, we’re not talking about well-located, separate parts of the brain.

Carroll rejects Fodor’s (1983) claim that the language faculty comprises a single language module in the mind’s architecture, and she sees Chomsky’s LAD as an inadequate description of the language faculty. Rather than accept that language learning is crucially explained by the workings of a “black box”, Carroll explores the mechanisms of mind more closely, and, following Jackendoff, suggests that the language faculty operates at different levels, and is made up of a chain of mental representations, with the lowest level interacting with physical stimuli, and the highest level interacting with conceptual representations. Processing goes on at each level of representation, and a detailed description of these representations explains how input is processed for parsing.

Carroll further distinguishes between processing for parsing and processing for learning, such that, in speech, for example, when the parsers fail to get the message, the learning mechanisms take over. Successful parsing means that the processors currently at the learner’s disposal are able to use existing rules which categorize and combine representations to understand the speech signal. When the rules are inadequate or missing, parsing breaks down; and in order to deal with this breakdown, the known rule that helps most in parsing the problematic item of input is selected and subsequently adapted or refined until parsing succeeds at that given level. As Sun (2008) summarises “This procedure explains the process of acquisition, where the exact trigger for acquisition is parsing failure resulting from incomprehensible input”.

Scholars from Krashen to Gass take ‘input’ and ‘intake’ as the first two necessary steps in the SLA process (Gass’s model suggests that input passes through the stages of “apperceived” and “comprehended” input before becoming ‘intake’), and ‘intake’ is regarded as the set of processed structures waiting to be incorporated into interlanguage grammar. The widely accepted view that in order for input to become intake it has to be ‘noticed’, as described by Schmidt in his influential 1990 paper, has since, as the result of criticism (see, for example, Truscott, 1998) been seriously modified so that it now approximate to Gass’ ‘apperception’ (see Schmidt 2001, 2010), but it’s still widely seen as an important part of the SLA process.

Processing Theories of SLA

Caroll, on the other hand, sees input as physical stimuli, and intake as a subset of this stimuli.

The view that input is comprehended speech is mistaken. Comprehending speech ..happens as a consequence of a successful parse of the speech signal. Before one can successfully parse the L2, one must learn it’s grammatical properties. Krashen got it backwards! (Carroll, 2001, p. 78).

Referring not just to Krashen, but to all those who use the constructs ‘input’, ‘intake’ and ‘noticing’, Gregg (in a comment on one of my blog posts) makes the obvious, but crucial point: “You can’t notice grammar”! Grammar consists of things like nouns and verbs, which, are, quite simply, not empirically observable things existing “out there” in the environment, waiting for alert, on-their-toes learners to notice them.

So, says Carroll, language learning requires the transformation of environmental stimuli into mental representations, and it’s these mental representations which must be the starting point for language learning. In order to understand speech, for example, properties of the acoustic signal have to be converted to intake; in other words, the auditory stimulus has to be converted into a mental representation. “Intake from the speech signal is not input to leaning mechanisms, rather it is input to speech parsers. … Parsers encode the signal in various representational formats” (Carroll, 2001, p.10).

Sorry for the poor quality of the scan.

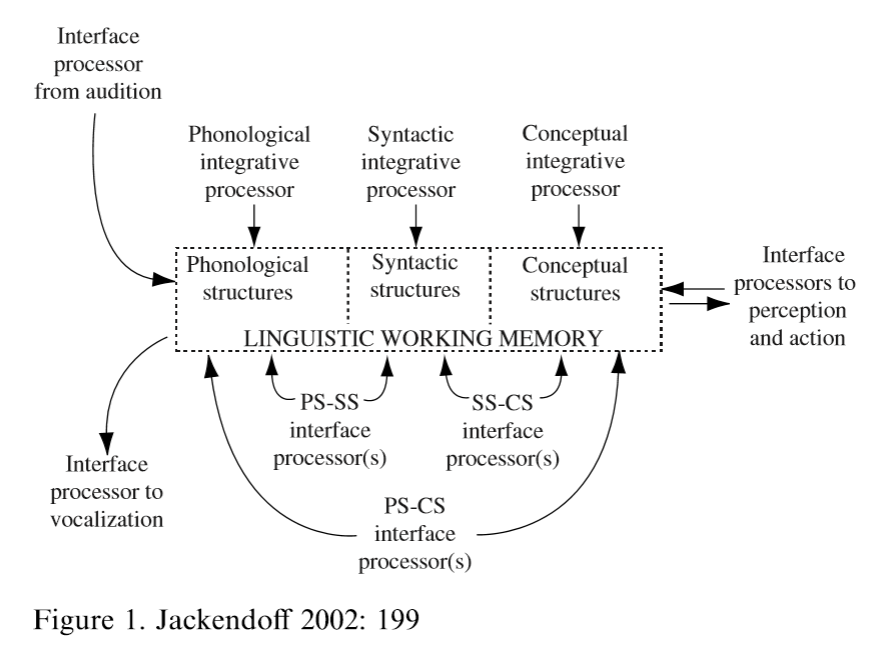

We now need to look at Jackendoff ‘s (1992) Representational Modularity. Jackendoff presents a theory of mind which contrasts with Fodor’s modular theory (where the language faculty constitutes a single module which processes already formed linguistic representations) by proposing that particular types of representation are sets belonging to different modules. The language faculty has several autonomous representational systems and information flows in limited ways from a conceptual system into the grammar via correspodence rules which connect the autonomous representational systems (Carroll, 2001, p. 121).

Jackendoff’s model has various cognitive faculties, each associated with a chain of levels of representation. The stimuli are the “lowest” level of representation, and “conceptual structures” are the “highest”. The chains intersect at various points allowing information encoded in one chain to influence the information encoded in another. This amounts to Jackendoff’s hypothesis of levels.

Here’s a partial model

Jackendoff proposes that, in regard to language learning, the mind has three representational modules: phonology, syntax, and semantics, and that it also has interface modules which, by defining correspondence rules between representational formats, allow them to pass information along from the lowest to the highest level. This is important for Carroll, because, as we’ll see, the different modules are autonomous and so there must be a translation processor for each set of correspondence rules linking one autonomous representation type to another.

What Carroll wants from Jackendoff is “a clear picture of the functional architecture of the mind” (Carroll, 2001, p. 126), on which to build her induction model. In Part 2, I’ll deal with the Induction bit, but we must finish Part 1 by looking at other parts of Jackendoff’s work.

The Architecture of the Language Faculty

In The Architecture of the Language Faculty, Jackendoff argues for the central part played in language by the lexicon. The lexicon is not part of one of his representational modules, but rather the central component of the interface between them. Lexical items include phonological, syntactic, and semantic content, and thus any lexical item is a set of three structures linked by correspondence rules. Furthermore, since lexical items are part of this general interface, there is no need to restrict them to word-sized elements–they can be affixes, single words, compound words, or even whole constructions, including MWUs, idioms, and so on. As Stephenson (1997) says: Simply put, the claim is that what we call the lexicon is not a distinct entity but rather a subset of the interface relations between the three grammatical subsystems. … Jackendoff’s proposal thus has the potential to provide a uniform characterization of morphological, lexical, and phrase-level knowledge and processes, within a highly lexicalized framework.

To bring this home, I offer two presentations by Jackendoff. In the first presentation, Jackendoff argues that lexis only – “linear grammar” – paved the way for modern languages. It’s eloquent, to say the very least.

The main argument is, of course, the importance of the lexicon, but I think this diagram is particularly interesting.

Never mind the details, just that comprehending starts with percepual stimuli and goes through various levels of representation from lowest to highest, while speaking starts with responding to stimuli actively and goes in the opposite direction.

In the second presentation, Jackendoff talks about mentalism and formalism. Please skip to Minute 49.

There a handout fot this which I recommend you download and then follow. Click here.

In this presentation Jackendoff argues that we should abandon the assumption made by generative grammar that lexicon and grammar are fundamentally different kinds of mental representations. If the lexicon gets progressively more and more rule-like, and you erase the line between words and rules, then you slide down a slippery slope which ends up with HPSG (Head-driven phrase structure grammar), Cognitive Grammar, and Construction Grammar, which, he says, is “not so bad”.

So, we may well ask, is Jackendoff a convert to UB theories? How can he be, if he bases his theory of Representational Modularity on the assumption of our possession of a modular mind? How can all this ‘mental representation’ stuff be reconciled with an empiricist view like N. Ellis’ which wants to explain language learning almost exclusively in terms of input from the environment? Part of the answer is, surely, that UB theory has a lot more mental stuff going on than it cares to recognise, but, in any case, I hope we can explore this further in Part 2, and I’d be very pleased if it leads to a lively discussion.

To summarise then, Jackendoff (2000) replaces Chomsky’s generative grammar with the view that syntax is only one of several generative components. Lexical items are not, pace Chomsky, inserted into initial syntactic derivations, and then interpreted through processes of derivations, but rather, speech signals are processed by the auditory-to-phonology interface module to create a phonological representation. After that, the phonology-to-syntax interface creates a syntactic structure, which is then, aided by the syntax-to-semantics interface module, converted into a propositional structure, i.e. meaning. Which is why, when a lexical item becomes activated, it not only activates its phonology, but it also activates its syntax and semantics and thus “establishes partial structures in those domains” (Jackendoff, 2000: 25). The same but reversed process takes place in language production.

What does Suzanne Carroll make of it all? See my posts “Carroll’s Induction Theory Parts 2 and 3” for more (Use the Search Bar on the right).

References

Carroll, S. (2001) Input and Evidence. Amsterdam, Bejamins.

Ellis, N. C. (2019). Essentials of a theory of language cognition. Modern Language Journal, 103.

Fordor, J. (1987) The Modularity of mind. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Gregg. K.R. (1993) Taking Explanation seriously. Applied Linguistics, 14, 3.

Jackendoff, R.S. (1992) Language of the mind. Cambridge, Ma; MIT Press.

O’Grady, W. (2005) How Children Learn Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Schmidt,R. (1990) The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics 11, 129–58.

Schmidt, R. (2001) Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp.3-32). Cambridge University Press.

Schmidt, R. (2010) Attention, awareness, and individual differences in language learning. In W. M. Chan, S. Chi, K. N. Cin, J. Istanto, M. Nagami, J.W. Sew, T. Suthiwan, & I. Walker, Proceedings of CLaSIC 2010, Singapore, December 2-4 (pp. 721-737). Singapore: National University of Singapore, Centre for Language Studies.

Stevenson, S. (1997) A Review of The Architecture of the Language Faculty. Computational Linguistics, 24, 4.

Sun, Y.A. (2008) Input Processing in Second Language Acquisition: A Discussion of Four Input Processing Models. Working Papers in TESOL & Applied Linguistics, Vol. 8, No. 1.

Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Truscott, John (1998). “Noticing in second language acquisition: a critical review” Second Language Research. 14 (2): 103–135.

thanks Geoff for reporting on this;

do you think Jackendoff or Carroll’s (computational) models are susceptible to the critique that such models in general are nothing more than re-descriptions of the problem? e.g. Bennett & Hacker (2014) On explaining and understanding cognitive behaviour https://aps.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ajpy.12080

Hi Mura,

I’ve just downloaded the article – pubished Australian Journal of Psychology 2015; 67: 241–250, BTW – and can’t really see its relvance having quickly looked at it. What makes you say that Jakendoff or Carroll’s theories are computational models?

hi, terms like ‘input’ ‘processing’ ‘parsing’, box diagrams showing flows of information?

Ah, right. Well all psycholinguistic theories of SLA using these terms are computational models, then. I thought you were referring to, for example connectionist models that tried to build programs whereby computers could demonstrate “linguistic knowledge”.

So, then, do you think Gass’s model, for example, is susceptible to the critique that it’s nothing more than a “re-descriptions of the problem”? If so, what problem does it do more than re-describe?

from what i understand the critique is computational models can be helpful in teaching & learning as they can describe regularities but they have minimal power to explain such regularities?

so for Gass, Bennett & Hacker might say (as they have for Levelt’s speech model, and Coltheart’s reading model) that it is simply re-describing the ability (defined as a potentiality) of learning a language into sub-abilities like apperception?

Hi Mura,

“Computational models have minimal power to explain the regularities in language. Gass is simply re-describing the ability of learning a language into sub-abilities like apperception”.

This stems, I think, from a misunderstanding of what theories do. Bennett & Hacker (2015) use the Oxford English Dictionary definition of explanation: ‘a statement or account that makes something clear’; ‘to make (an idea or situation) clear to someone by describing it in more detail or revealing relevant facts’

Theories of SLA don’t attempt to ‘explain’ in this OED sense, and they certainly don’t attempt to explain the regularities of language. As I’ve already said in the post, two different types of theory are required: a property theory which describes grammar (I use the word “grammar” in the sense that linguists use it; viz., “knowledge of a language”); and a transition theory which explains how this knowledge changes and develops in the mind of the learner. As Gregg puts it, a transition theory answers the question “How does the mind change from a state of not knowing X to knowing X, where X can be any part of linguistic knowledge from syntax to pragmatics or what have you”. A transition theory is a causal theory and it tries to explain a “Why” or “How” question. For example, the Processability Theory (Pienemann, 1998) attempts to answer the question “How do L2 learners go through stages of development?”

Causal theories about non-observable phenomena like the development of interlanguages need theoretical constructs. They name the non-observable phenomena – interlanguages, appreception, intake, noticing – and then they make constructs from them. These constructs are theory-laden – they serve the theory by helping to pin down the non-observable phenomena that we want to examine so that the theory can be given empirical content and thus tested.

So yes, Gass’s transition theory, like those of Chaudron, Krashen, Sharwood Smith, Pienemann, Long, and Towell & Hawkins, all attempt to explain the same, or similar, phenomena, and yes, they all use constructs to build a mechanism that computes (calculates, reckons, makes sense of) incoming sensory data and produces fluent speech. And they all have the same aim, namely to explain various phenomena, including a) transfer of grammatical properties from the L1 mental grammar into the mental grammar that learners construct for the L2; b) staged development – L2 learners go through a series of “transitional stages” towards the target language; c) systematicity – in the growth of L2 knowledge across learners; d) variability in learners’ intuitions about, and production of, the L2 at various stages of L2 development; e) incompleteness – most L2 learners do not achieve native-like competence. But they’re all different and often incompatable, and, in Carroll’s view they’re all wrong! Which is why I find Carroll’s theory so interesting. BTW, they’re interesting not just to academics – they have enormous implications for ELT.

To claim that such theories do no more than “re-describe the ability to learn a language into sub-abilities” is to claim that “the ability” to learn a language has already been adequately described, and that there’s no need to look for “sub-abilities”. This is the claim of the cognitive psychologists, who you (inexplicably, in my horrified opinion!) seem to have climbed into bed with. They make the preposterous claim that “experimental psychology can correlate physiological events and processes with behavioural manifestations, avowals and reports of thought and experience” through the method of “connective analysis”. Bennett & Hacker’s (2015) article seems to me very little more than hand waving – even using the OED definition of explanation, it does nothing, IMHO, to explain SLA.

All this, is, of course, just another manifestation of the new empricism, now backed up with hopelessly inadequate apppeals to new knowledge about what’s going on in the brain. What are “the regularites in language” that you, citing Bennett & Hacker (2015), refer to? Are they supposed to be a property theory, that is, a description of language knowledge? And how can “correlating physiological events and processes with behavioural manifestations, avowals and reports of thought and experience” explain the phenomena that a theory of SLA should explain? We’re going right back to the 1950s, where language knowledge was described by structural linguistics, a corpus-based descriptive approach, providing detailed linguistic descriptions of hundreds of different languages, and language leaning was explained by appeal to behavioural psychology. The only difference is that we now have cognitive psychologists, whose delight in obsfucation makes reading Carroll seem like a walk in a pleasant park.

Very best wishes to you Mura – stay safe!

A quick respone – regularities refer to what SLA studies can show, e.g. if we give such input to these students in this way they learn that thing

What does giving input to students mean? How do you know they learn “that thing”? In any case, if you look at the articles published in the top 5 SLA journals over the last 10 years, you’ll see that SLA studies a lot more than regularities. The best articles either propose a hypothesis which attempts to answer a well articulated question about 1 of the phenomena I mentioned, or they do replication studies to test those hypotheses, or they do some critical evaluation of published work.

point about regularity was just to clarify it was not reference to language regularities; there are a lot things to say but would clutter your post here will see if i can do a post on it!

I look forward to reading the post!

This post is the reason why I always come back for more.

Not that it gets easier. But that is part of the fun.

Tom

Hi Tom, Good to see you back.

Pingback: The Enigma of the Interface | What do you think you're doing?